More information

About the center

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri (CTP), part of The Bancroft Library, promotes new research about the largely unstudied Tebtunis Papyri.

The mission of CTP is to enhance understanding of, provide context for, and give access to the Tebtunis Papyri collection. Toward these goals, CTP supports international collaboration in deciphering the papyri and training for students who will carry this task into the future.

CTP was created in 2000 as an Organized Research Project supported by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research. Additional support is provided by The Bancroft Library, the Departments of Classics and Art History, and outside donors. CTP is guided by an advisory committee representing the Departments of Classics, Near Eastern Studies, and History, the Graduate Program in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology, and The Bancroft Library.

Dr. Todd Hickey, Associate Professor of Classics, Papyrologist, and Curator, oversees the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri. Since his arrival at UC Berkeley in 2001, CTP has made steady progress in the conservation, digitization, decipherment, and publication of the Tebtunis papyri. By training students in the care and translation of these ancient texts, CTP has added papyrology to the strengths of the already world-class Classics and Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology programs at Berkeley.

Photo: Crocodile mummies from Tebtunis found in 1899/1900

About the collection

About the Tebtunis Papyri

The Tebtunis Papyri were excavated at the dawn of the 20th century (winter 1899/1900 CE) at the site of the ancient Graeco-Roman city of Tebtunis, located in the Fayum basin of Egypt. The expedition to Tebtunis, which was led by the British papyrologists Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, was financed for the University of California by Phoebe Apperson Hearst.

Thus, the collection is now held by The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. It is the largest collection of papyrus texts in the Americas. The collection has never been counted and inventoried completely, but the number of fragments contained in it exceeds 26,000.

About the town of Tebtunis

Ancient Tebtunis, now known as Umm el-Breigat, is situated in the southwest corner of the Fayum basin in Egypt. Its history covers some 3,000 years, from the early second millennium BCE into the 13th century CE. Its best documented epoch is the Graeco-Roman period, roughly spanning the third century BCE through the third century CE.

Sobek, an ancient Egyptian crocodile god with complex and fluid characteristics, was important throughout the Fayum. Tebtunis had an important temple to Sobek marking the center of town. There they called their reptilian deity “Soknebtunis,” meaning “Sobek, lord of Tebtunis.”

The importance of Soknebtunis in Tebtunis explains why the first excavations there — carried out by Grenfell and Hunt for the University of California in the winter of 1899/1900 — unearthed many papyri from both human and crocodile mummies buried in the town’s necropolis. Some of these papyri originated in neighboring villages, such as Kerkeosiris and Oxyrhyncha, and then were used in the mummification process in Tebtunis.

Other papyri from the excavation were found in the temple and in the surrounding town, rather than in mummy cartonnage. The Bancroft Library holds papyri texts from the temple’s library and notary office, family archives of various village dignitaries, and much more. Research into this rich corpus of documents (and related archaeological objects) has been undertaken at various institutions worldwide and continues to enrich our understanding of the administrative and socioeconomic history of the entire ancient Mediterranean world.

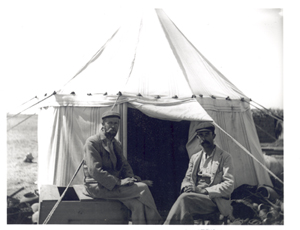

Photo: Bernard P. Grenfell (right) and Arthur S. Hunt in Tebtunis, 1899/1900; courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society

Timeline of 20th century excavations in Tebtunis

1899/1900 CE (winter): Grenfell and Hunt excavate the Tebtunis Papyri for the University of California, Berkeley.

Circa 1910 - 1930 CE: Papyri from Tebtunis were offered for sale on the antiquities market in Cairo, indicating that Egyptians were carrying out illegal excavations at the site. The University of Michigan acquired large batches of papyri connected with the notary office of Tebtunis. The Carlsberg Foundation in Copenhagen acquired a considerable number of demotic Egyptian literary texts from the library of the temple of Soknebtunis at Tebtunis. The University of Giessen and the University of Oslo also purchased papyri from similar sources.

1930s CE: An Italian expedition led by Anti, Bagnani, and Vogliano yielded more demotic Egyptian literary texts from the temple library. Their team made a spectacular discovery in a building that was soon called the “Cantina dei Papiri”; here, besides a roll with an ancient scholarly commentary on the poems of Callimachus (Diegeseis), the excavators found hundreds of documentary papyrus texts.

1989 CE - present: Excavations have been resumed at Tebtunis by a joint expedition of the Papyrological Institute of the State University of Milan and the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale in Cairo.

Collection history

Unlike the other major papyrus collections in the United States, the Tebtunis papyri come from a single archaeological expedition, from four distinct sites in and around Tebtunis. Therefore, the history of the collection as a whole can be described easily. This history centers around three locations: Tebtunis, where the papyri were found; Oxford, where the publication of part of the collection was undertaken; and Berkeley, the present home of the collection.

Tebtunis (1899/1900)

The saga of the Tebtunis papyri commenced on December 3, 1899, when Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt arrived at the remains of what would soon prove to be Tebtunis. They had been hired by George A. Reisner to excavate for the University of California with funds generously provided by Phoebe Apperson Hearst.

Grenfell and Hunt’s first objective was the town of Tebtunis itself. In the course of a few weeks they explored the remains of the town and a temple complex that would turn out to be the temple of the crocodile god Soknebtunis (“Sobek, lord of Tebtunis”). In both locations they found a wealth of papyri. George Reisner informed Phoebe Hearst on January 2, 1900, that he was “very happy to report extraordinary success on the part of Grenfell and Hunt in the Fayum,” having found in less than a month “nearly as much as in any ordinary year.”

In early January 1900, Grenfell and Hunt moved to the huge necropolis in the desert south of Tebtunis. Here they sought human mummies, in particular the cartonnage covering these mummies. A few years earlier, this cartonnage had been proven to be a possible source of texts, when Sir Flinders Petrie discovered that discarded papyri were sometimes employed in its manufacture (think “papyrus mâché”), especially during the Graeco-Roman era. Grenfell and Hunt successfully unearthed more than 50 mummies in whose cartonnage discarded papyri had been used.

While searching for papyrus-laden mummy heads and pectorals, Grenfell and Hunt discovered a cemetery of mummified crocodiles bordering the necropolis of human mummies. At that time, crocodiles were considered to be objects without any archaeological worth whatsoever.

This assessment soon changed, however, when on January 16, 1900, one of Grenfell and Hunt's workmen, “disgusted at finding a row of crocodiles where he expected sarcophagi, broke one of them in pieces and disclosed the surprising fact that the creature was wrapped in sheets of papyrus.” After this discovery, Grenfell and Hunt devoted the remainder of the season to clearing out part of the crocodile cemetery. Although they unearthed more than 1,000 of these mummified reptiles, only 31 appeared to have been mummified with the help of discarded papyri. Grenfell and Hunt's assistant definitely had a stroke of luck.

In the summer of 1900, finally, the discoveries of the season at Tebtunis were presented to George Reisner and divided: all artifacts were shipped to Berkeley, and are currently housed in the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology; most papyri written in demotic Egyptian remained in Egypt where they were published in 1908 by W. Spiegelberg in P. dem. Cairo II; papyri written in Greek (along with some in Egyptian and a few in Latin) went to Oxford, where Grenfell and Hunt prepared them for publication.

Oxford (1900-1938 for most of the papyri)

Grenfell and Hunt, with the help of J. G. Smyly, managed to publish the first volume of The Tebtunis Papyri just two years after their discovery. This first volume contained documents from the crocodile mummies.

In 1907, Grenfell and Hunt published the second volume, which was devoted to the papyri from the town and temple of Tebtunis itself.

The publication of a third group of papyri was delayed by the illness and eventual death of Grenfell, and then by the death of Hunt. In 1933, however, Oxford finally published a first batch of material found in the cartonnage of human mummies with the preparation assistance of J. G. Smyly. Oxford published the second batch in 1938 with preparation help again from Smyly and with editorial help from C. C. Edgar.

Meanwhile in Berkeley, questions arose as to the whereabouts of the promised Tebtunis papyri. In 1938, therefore, Oxford shipped the papyri to their intended home at the University of California at Berkeley.

Berkeley (1938 -)

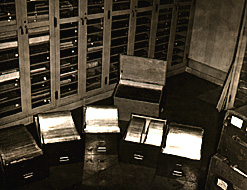

In 1938, most of the Tebtunis papyri arrived in Berkeley and became part of the Library. Staff and faculty were surprised to find that, more than 30 years after their discovery, no measures had been taken to preserve them. They were simply inserted between pages of old issues of the Oxford Daily Gazette and piled up in the tin boxes used by Grenfell and Hunt.

In 1940, the University of California sought the services of a papyrologist. Since no such specialist was to be found in Berkeley, the university hired Edmund Kase, Jr., from Grove City College in Pennsylvania. Through the summer Dr. Kase was to put the collection in order, providing guidance for preservation and cataloguing.

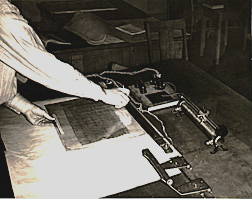

Kase took 1,705 fragments from the tin boxes, catalogued them, and mounted them. The material that Kase selected to mount the papyri was a plastic called Vinylite. In a letter to Prof. H. R. W. Smith, Kase enthusiastically enumerated the advantages of this new material: it was unbreakable, it took up less storage space than glass, and it was light.

Fragments beyond the 1,705 that Kase mounted remained loose in the tin boxes until the 1970s.

The 1970s

In the early seventies, work on the Tebtunis papyri resumed at The Bancroft Library. Efforts completed by the late John Shelton and James Keenan culminated in the publication of a fourth volume of The Tebtunis Papyri. These were the papyri that had only been briefly described at the end of the first (crocodile papyri) volume.

The renewed attention to the Tebtunis papyri also made painfully clear what time had done to the collection. It became apparent that Vinylite had enormous disadvantages hitherto unknown. Light and unbreakable as predicted by Kase, the material also proved to be quite flexible. This flexibility caused fragments of the papyri to break off inside the mount, and these fragments tended to move around due to the static electricity generated by the two sheets of plastic. This damage could not, and cannot, be repaired without breaking the mount because the mounts were heat sealed. Another disadvantage of the Vinylite was its susceptibility to scratching.

While working on the papyri, Shelton remounted some of the papyri under glass. He also urged the library to take measures to prevent further damage to the papyri.

In 1979, Dr. Elbert Wall visited The Bancroft Library on behalf of the American Center of the International Photographic Archive of Papyri. Not only did he photograph the 1705 mounted and catalogued fragments, he also removed more than 21,000 papyrus fragments from the tin boxes in order to photograph the most important of them. He then stored them in acid-free folders, ten fragments to a folder. Unfortunately, Wall did not have sufficient time to remove all of the papyri from the tin boxes.

In the late 1970s, then, the situation with regard to the Tebtunis Papyri Collection was as follows:

- About 1,600 of the mounted and catalogued papyri were still in their Vinylite mounts.

- The remainder of them had been remounted in glass.

- More than 21,000 fragments were crushed together in acid-free folders.

- There still remained a number of tin boxes with papyrus fragments, including part of an unopened roll.

APIS (1996-2013)

Thanks to a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, work on the Tebtunis papyri has resumed once again.

In 1996, The Bancroft Library began to catalogue, conserve, and digitally image the collection as a participant in the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS).

As of July 1, 2013, the host and steward of canonical APIS data is papyri.info, which is served by the DC3 and Duke University Libraries.

About the database

Database contents

The Tebtunis Papyri Database contains detailed records for several thousand papyrus documents, and a small group of ostraka. This project is ongoing, so only a fraction of the Bancroft Library’s papyrus collection is cataloged to date, and some database records are incomplete. We continually add to and update this growing resource.

Digitization of papyri currently indexed has been prioritized according to one or more of the following criteria:

- Risk of physical damage. Many of the papyri housed in vinylite (plastic) had suffered severely from their mounts. These texts have now been cleaned and placed under glass. The papyri most at risk were those that came from crocodile cartonnage.

- Representation. We have tried to include a sample of each category of papyrology in the database to show the depth of the collection.

- Subject. The texts in the collection are of interest to papyrologists and historians of Graeco-Roman Egypt, Egyptologists, historians of the ancient world, philologists, historians of law, etc. Texts have been selected to demonstrate the collection's relevance to these and other fields.

The papyrus fragments

Each database record contains information about one intellectual item, a text. Generally, each papyrus fragment contains one text. In a number of cases, however, multiple texts exist on one fragment, or one text carries across several fragments.

The physical properties of each intellectual item (text) are presented in detail in each record, as are the precise relations with other physical items (context).

The design of each record

The contents of the database are presented on two levels.

The generalized level includes:

- Holding institution

- Call number

- Author

- Title

- Modern date

The detailed level includes:

- Holding institution

- Call number

- Shelving information, including number of frames

- Author

- Type of text (for documentary texts), or Title (for literary texts)

- Section/Side

- Publication/Side

- Connections (to other known texts)

- Number of fragments

- Dimensions (sizes)

- Number of (columns and) lines

- Physical properties (margins; sheet joins; secondary information written on the papyrus)

- Paleographic description

- Internal date

- Modern date

- Origin

- Provenance (crocodile or human mummies, town, etc.)

- Language

- Content

- Context (if part of an archive or dossier)

- Persons (individuals mentioned in the text other than the author)

- Geographical (places mentioned in the text)

- Publications

- Bibliographical information, including corrections

- Translation (if available)

The detailed view is followed by images of the papyrus, when available.

Little studied texts

There is also a large number of “brief records” in the database. These represent chiefly unmounted fragments yet to be studied in detail. They are mostly documentary texts in Greek or Demotic. The approximate date or period of the fragment is given, along with its provenance, when known.

Reproduction of images in the database

Use or reproduction of original papyrus fragments, or images thereof, may be made only by permission of the Curator.

All requests for permission to publish texts or reproduce images must be submitted in writing to:

Todd Hickey

Curator, Center for the Tebtunis Papyri

The Bancroft Library

University of California

Berkeley, CA 94720-6000

Advisory committee

Professor S. Elm, History and Ancient History & Mediterranean Archaeology (AHMA)

Professor M. Griffith, Classics

Professor E. S. Gruen, History, Classics, and AHMA

Professor C. Hallett, Art History, Classics, and AHMA

Professor A. A. Long, Classics

Professor D. J. Mastronarde, Classics, Committee Chair (CTP Director 2001-2011)

Professor N. Papazarkadas, Classics and AHMA

Professor C. A. Redmount, Near Eastern Studies and AHMA

Professor E. Tennant, Former Director of The Bancroft Library

Professor A. W. Bulloch in memoriam, Classics