Hannah Tashjian had a revelation.

She was working with a letter handwritten by Mark Twain in 1876. The missive was glued on its left edge to a slightly thicker piece of paper, probably in an attempt to protect it, recalled Tashjian, the interim head of preservation at the UC Berkeley Library. The backing forced the viewer to flip the letter like the page of a book to read the text on the reverse side, which made the precious artifact more difficult to study, and put it at greater risk of damage.

When Tashjian detached the backing, she discovered something unexpected — a semicolon that had been obscured by the adhesive.

“I got to reveal a semicolon that Mark Twain wrote,” she said. “I might have been the first person to see that punctuation mark in more than 100 years. That was an exciting moment.”

Bob Hirst, general editor of The Bancroft Library’s Mark Twain Papers and Project, called the discovery “the sort of thing that makes your whole week,” noting that it was particularly relevant in regard to Twain, who was known to be protective of punctuation.

Revelations are part and parcel of the work happening every day in the Library’s Preservation Department. It’s one component of an often unseen profession, which steps into the spotlight this week with the launch of a new exhibit, Shelf Life: Preserving the Library’s Collections. The revelatory exhibition, on display in the Doe Library’s Brown Gallery through January, showcases the tools, techniques, and terminology of preservation. An online version is also available.

“(The exhibit is) a behind-the-scenes look at some of the invisible work that goes into making sure that library collections are not lost to time,” Tashjian said. “I’m excited for people to learn more about the interesting and obscure aspects of what we do.”

Opening up the past

Among the most unique of those tasks is working with 2,000-year-old papyrus fragments from ancient Egypt through Bancroft’s Center for the Tebtunis Papyri.

Papyri are sheets of material that were written on and sometimes reused later to embalm mummified remains. The sheets contain text detailing everything from property records to poetry. In fact, the preservation team once worked with a papyrus fragment that contained text from Homer’s Iliad.

Martha Little, a conservator in the department’s Conservation Treatment Division, said it is gratifying to remove dirt, realign fibers, or unfold creases that reveal script that is several thousand years old. But even more importantly, it is vital to understanding history.

“What we do with the papyri is important to researchers around the world who are studying and writing about ancient Egypt,” she said. “Our work helps them do theirs.”

Both Little and Tashjian find joy in the meticulous process of preservation, whether they are working on an item of historical importance or something more ordinary.

“I really like conserving the sort of ephemeral and quotidian things that are most likely to get forgotten or overlooked,” Tashjian said. “Conserving that stuff is very important, because of course everyone is going to make sure a Shakespeare folio is taken care of, but who is going to look out for the little guy — the interesting doodles on a cocktail napkin written by some luminary in a bar in San Francisco?”

Back to the future

Besides making artifacts from special collections accessible to today’s scholars, the department ensures that current materials will be available to the scholars of the future.

That means protecting and repairing items from the circulating collections, such as books or periodicals regularly used by Library visitors. When a book is returned damaged, the team selects the best method of repair, oftentimes consulting with other library units. The book could, for example, be sent to the University of California Bindery in Richmond, where it will be re-bound with a durable cover. If a book is missing a page, the team can replace the page with a photocopy.

Serials such as magazines are often bound together as volumes to ensure individual issues don’t get misplaced. For newspapers, which tend to deteriorate quickly, the team will often recommend converting an item to microfilm, which guarantees a longer life, while also saving space.

Rosemary Sallee, the head of the Bindery Preparation and Preservation Replacement divisions, emphasized the value of preserving paper collections.

“There are whole language groups where that literature and that scholarship isn’t well represented in the digital world,” she said. “Publishers are not producing these books in digital formats for libraries to acquire. Likewise, a lot of the newspapers that we microfilm are not available digitally. So preserving print, binding it, or filming it is still really important.”

Sallee noted a recent example in which her team facilitated the microfilming of a series of Kurdish newspapers from Turkey. The media outlet was shut down by the government because of its political content, Sallee recalled, but other successor newspapers started up publication soon after to ensure that a unique journalistic voice wasn’t silenced.

“Being able to preserve those items that we’re going to look back on, something very historic, and something of great interest to researchers — that is really special to me,” she said.

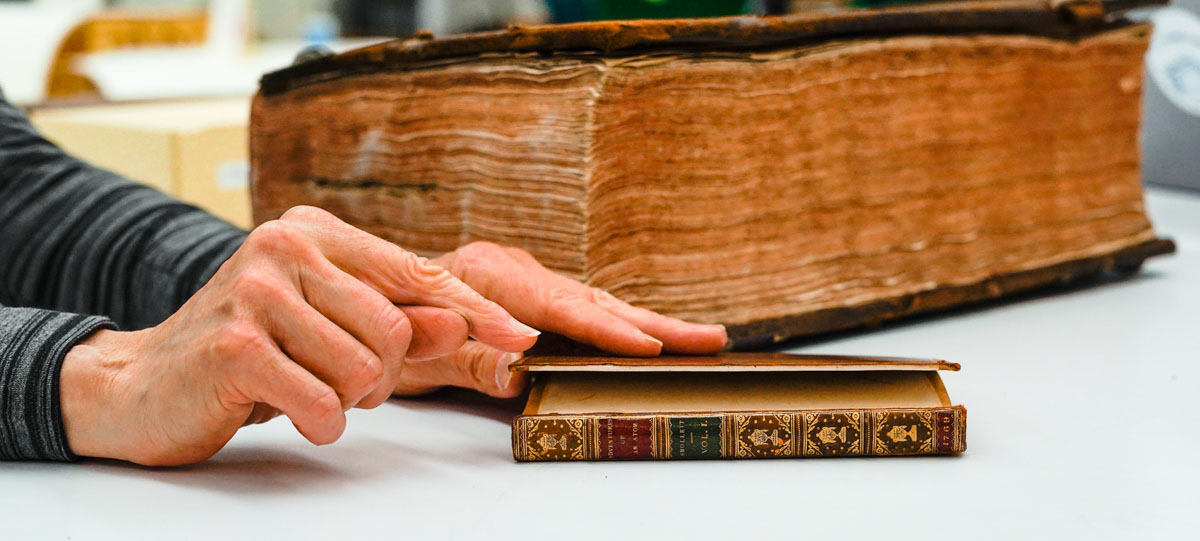

One size does not fit all

John Shepard, the curator of music collections at the Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library, lauds the Preservation Department’s work. With a plethora of priceless musical scores and texts under his care, he appreciates the assistance in keeping materials protected and accessible.

Shepard said the department assists his work in many ways. The team maintains a disaster response plan for the library (and all of the university’s more than 20 libraries) that prioritizes which items conservators would save first in the event of a flood, fire, or other emergency. The team also monitors the climate in the library’s special collections, regularly collecting temperature and humidity readings to ensure the best possible environment.

The most consistent support the team offers is creating customized preservation solutions.

“I know they are busy, so I try to go in with very minimal requests,” Shepard said. “I ask them to just put something in a basic box for me. But they really care, so they tend to want to go further. ‘Do you want us to repair this thing here?’ or ‘How do you want to handle this?’ I’m always very impressed by their work.”

As an example of the team’s approach, Shepard cites a manuscript of Handel’s opera Siroe, which was copied by a scribe around 1740. The manuscript came to the library disbound and broken into several pieces, with the first page detached. The preservation team put that first page into a Mylar sleeve, while the rest of the pages were placed in enclosures by groups, keeping them protected and organized.

In some cases, conservators decide the best course of action is not to repair an item at all.

“We ask a lot of questions about the item, so we can take its unique situation into consideration,” conservator Erika Lindensmith said. “Sometimes it’s important to preserve the history of the object. For example, we might leave the spine exposed so researchers can see how that book was made.”

Tashjian said one of the fundamental principles in conservation is to think carefully about the ways in which an artifact may be permanently changed by a treatment.

“We have the best intentions in conserving collections, but we can’t predict the future,” she said. “When we intervene with an item, we need to make sure our work can be undone, so that in 300 years, when they are like, ‘Why did they do that?’ they’ll be able to undo it.”

Thankfully, those interested in the processes — and mysteries — of the preservation profession don’t need to wait nearly so long to learn more. With the new exhibit now open, people can see for themselves the unique mix of art, science, and magic that is library preservation.