This is not your typical final exam.

Art history students at UC Berkeley are putting their semester-long learning on display this week with Letters | الحروف: How Artists Reimagined Language in the Age of Decolonization — a thought-provoking exhibit opening March 13 in Doe Library’s Brown Gallery.

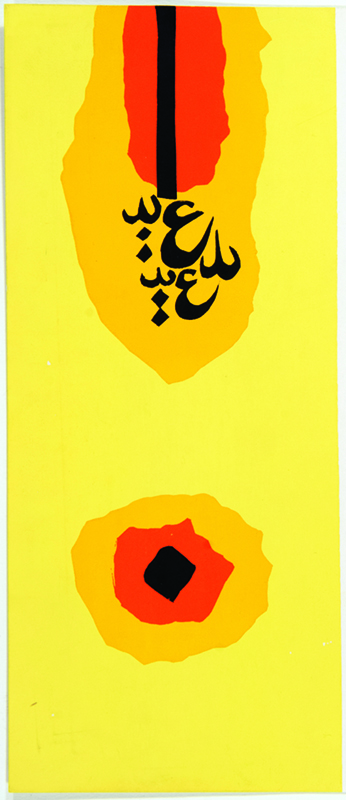

In doing so, the students invite visitors to experience the transnational art phenomenon known as calligraphic modernism (circa 1960-89), which saw artists from the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, without knowing each other, turn to the forms of the Arabic alphabet as elements in modernist art. The artists worked amid the tumultuous backdrop of the postcolonial era.

Letters | الحروف How Artists Reimagined Language in the Age of Decolonization

Where: Doe Library’s Bernice Layne Brown Gallery

When: March 13, through Sept. 1, 2023 (4 p.m.), with exceptions; the gallery is open the same hours as Doe Library. Check the hours before you go.

Cost: Free

Opening reception: March 15, 5 p.m., Morrison Library; pre-reception Arabic calligraphy workshop, 2:30 p.m., Doe Library

“The question at the heart of the exhibit is how to understand the historical circumstances that prompted the turn to letters,” said Anneka Lenssen, an associate professor in the History of Art Department, who developed the fall 2022 class to complement her research interests. “The students will be answering that question by putting together cases on specific artists who made that choice, showing artwork, and then selecting materials from the Library’s collections that can further elucidate both the work and the artists’ decisions.”

The exhibit prioritizes learning on several fronts. The project aims to educate visitors about a significant art phenomenon by elevating the voices of its featured artists. It also supports hands-on learning for student curators who gained experience in creating a public exhibition while also conducting intensive research about art from a region that some of them were not as familiar with.

Mohamed Hamed, the Middle Eastern and Near Eastern studies librarian, who provided support for the exhibit portion of the course, said the learning goes even deeper.

“Every artist has a story to tell; every piece of art has a story to tell,” he said. “So all of that (research) will give them ideas about what other parts of the world actually look like, in terms of politics, economy, history, religion, and social conditions. One piece of art can do part, some, or all of that.”

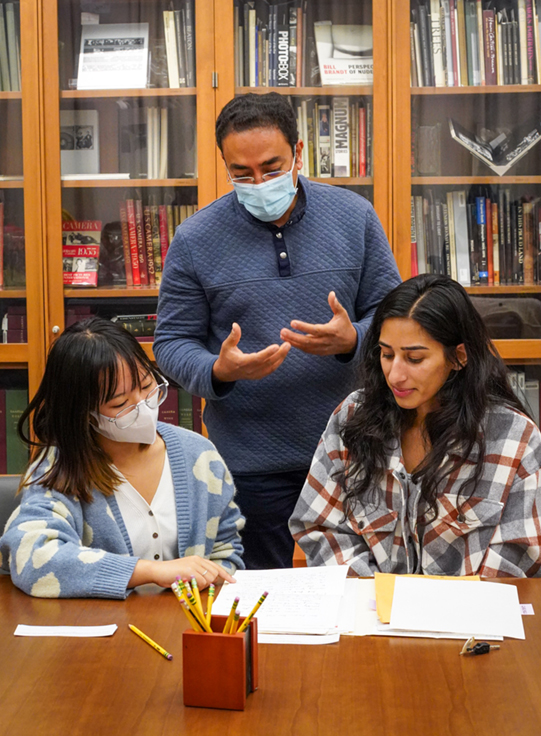

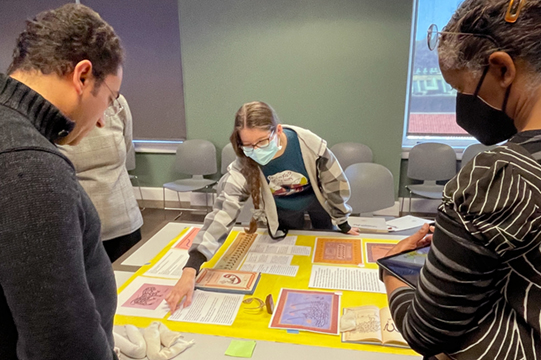

Top to bottom: Clockwise from left: Middle Eastern and Near Eastern Studies Librarian Mohamed Hamed, standing, discusses research materials related to artist and writer Etel Adnan; researchers inspect a photograph; students also met another day with Hamed, left, and Exhibits and Environmental Graphics Coordinator Aisha Hamilton, right, to finalize exhibit case plans. (Photos by Jami Smith/UC Berkeley Library and from Lynn Cunningham)

Students as curators

Hayley Zupancic, a third-year student majoring in political science and art history, called the class “one of the best” she’s taken at Berkeley. She lauded the practical experience gained in curatorial processes and the opportunity to grapple with questions illuminated by the exhibit.

“We talk about how artists navigate a political climate in this postcolonial world, where many nations were not allowed to form their own identities,” she said. “I think that we cover a lot of very heavy topics in terms of the damage that colonialism has done … and how these artists navigate their own national and cultural identity, but also are in conversation globally.”

Zupancic, who aspires to be a lawyer in the art world, worked with her research partner to unravel a minor mystery for their case on Turkish artist and poet Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu. (Although Turkey was never colonized, the country was impacted by the overall region’s postcolonial political realignments.)

A mosaic created by Eyüboğlu, titled The Bosporus, is on display at Stephens Hall, on the Berkeley campus. A plaque near the work notes the title, artist, donor, and year of installation, but until this class project, little more was known about it.

“We’ve basically reconstructed, as best we can, the history (of the work) from production until now,” Zupancic said. As it turns out, the work was originally commissioned for a San Francisco home, and was created by Eyüboğlu and students in 1962, while the artist was a visiting associate professor at Berkeley. The mosaic was donated to the university in 2009, and installed in 2011.

In the work, Eyüboğlu uses swooping lines (reminiscent of the Arabic letter و — or vav in Ottoman Turkish) to form the eponymous sea strait. Students detail in the exhibit how Eyüboğlu was able to balance the traditional and modern by blending the mosaic medium with a modernist abstraction style.

Another featured artist is Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, commonly known as Sadequain, who is often referred to as the most famous Pakistani artist to date.

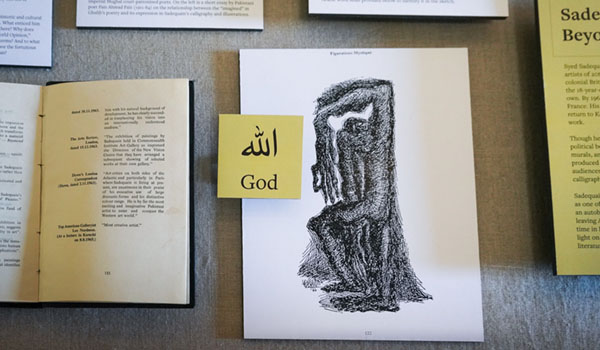

In his work across multiple mediums, Sadequain fully embraced the legacy of South Asian Muslim cultures while also producing pieces in the European style of post-cubism. His works for European audiences often included hidden or inconspicuous Islamic religious motifs. In an untitled sketch from 1966, for example, Sadequain has a figure use its hands to spell out the word “Allah,” or الله, meaning “God” in Arabic.

Top to bottom: Left to right: A page from the Sadequain book Figurations Mystique is displayed in the exhibit; a visitor walks through the exhibit, which will be on view through August. (Photos by Jami Smith/UC Berkeley Library)

Viv Kammerer, a third-year student majoring in art history, film and media, and ancient Middle Eastern languages and cultures, studied Sadequain’s oeuvre.

Kammerer and their research partner, Murtaza Hiraj, who is from Pakistan, spent a lot of time considering how they wanted to portray the South Asian country, in light of Sadequain’s transnational work.

“When you think (of the) Middle East, (Pakistan) is not always the first country that comes into your head,” Kammerer said, “and because (Sadequain’s) work looks very abstracted or modern, we want to frame it, not in a way that’s like, ‘Look at this art that looks like it could be European that’s coming from Pakistan,’ or, ‘look at this calligraphy that isn’t super obvious.’

“We want to just show … his work on his own terms, as much as we can, without getting too bogged down in the political or kind of art historical tropes that are placed upon Middle Eastern art.”

Partners in the Library

All of the primary works featured in the exhibit — representing a wide swath of artists from across the region — were drawn from the Library’s holdings. UC Berkeley’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies also provided resources.

Art Librarian Lynn Cunningham, who contributed to the original exhibit proposal and was embedded in the class at different points throughout the semester, said that she and Hamed helped the students sharpen their research through individual and group skill-building sessions. Hamed assisted with Arabic language translation as well.

Cunningham recounted a class trip to The Bancroft Library, where students viewed the archive of the Lebanese writer and artist Etel Adnan, who lived in the Bay Area.

“The students were able to experience what it was like to conduct research in an archive and work with unique and primary sources,” Cunningham said.

Students also benefited from the guidance of Aisha Hamilton, the Library’s exhibits and environmental graphics coordinator, who helped the curators create “a visual portfolio of their academic story.”

“Exhibits motivate viewers to explore more on the topic,” she said, “and find their own story through the research.”

Hamilton was impressed by what the students accomplished on a project that required immense levels of thought, perseverance, and follow-through, especially in a short time frame.

Lenssen agreed. “I can’t wait to enter Doe and see people looking at the exhibition that my students made,” she said. “But equally, as a scholar, I am really excited about how 17 hardworking, committed students are going to contribute new knowledge to the world of modern art in the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa.”

Students in the course created a short documentary film on the Sacramento-based Iraqi artist Saleh al-Jumaie, above. It is included in the exhibit.