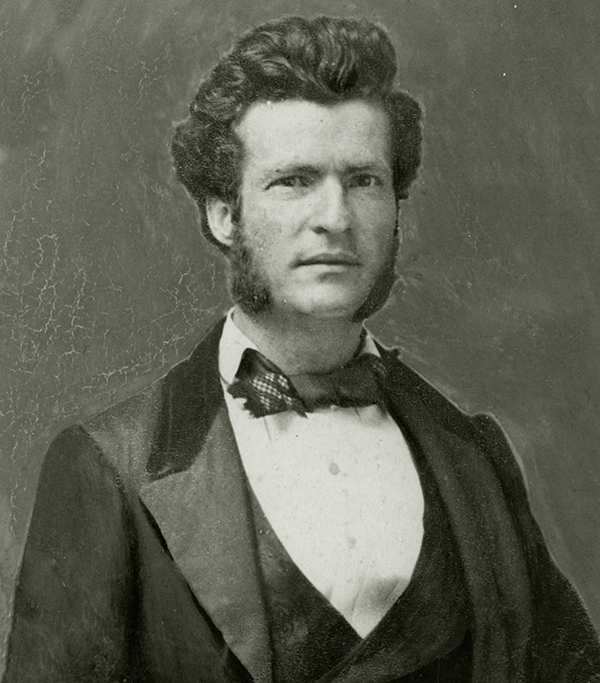

More than a century after his death, Mark Twain is still finding ways to surprise.

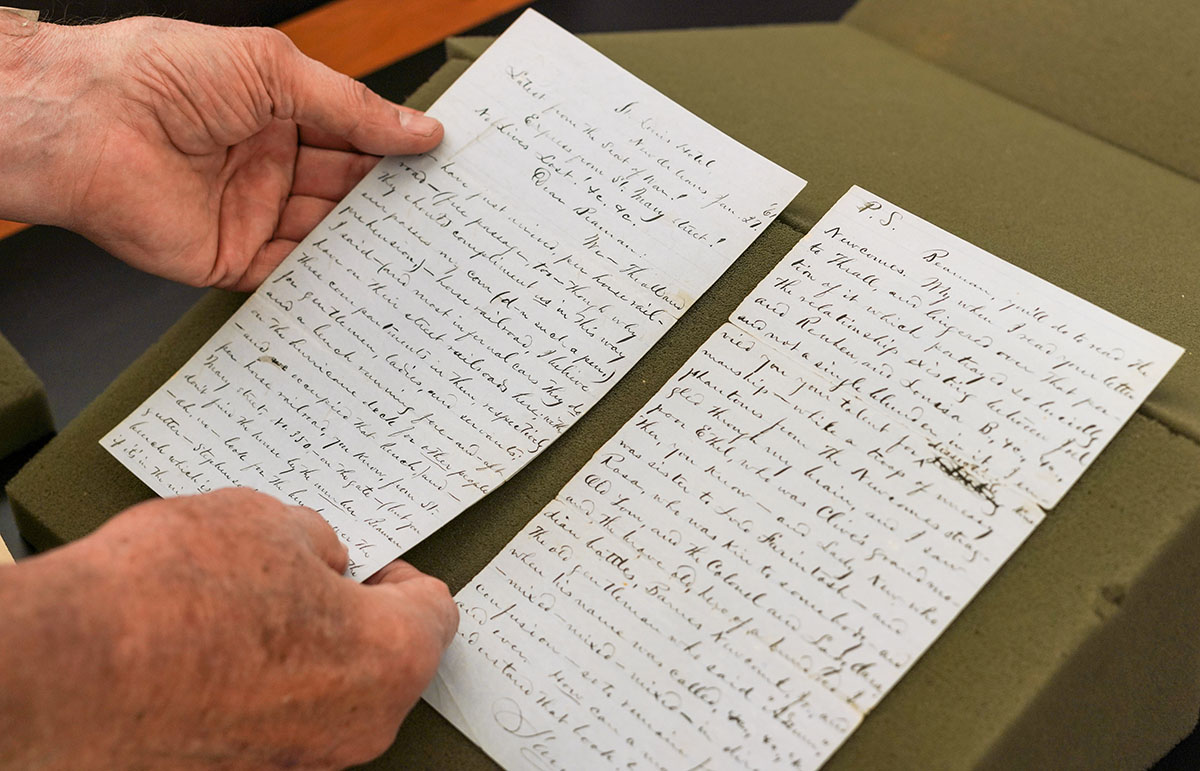

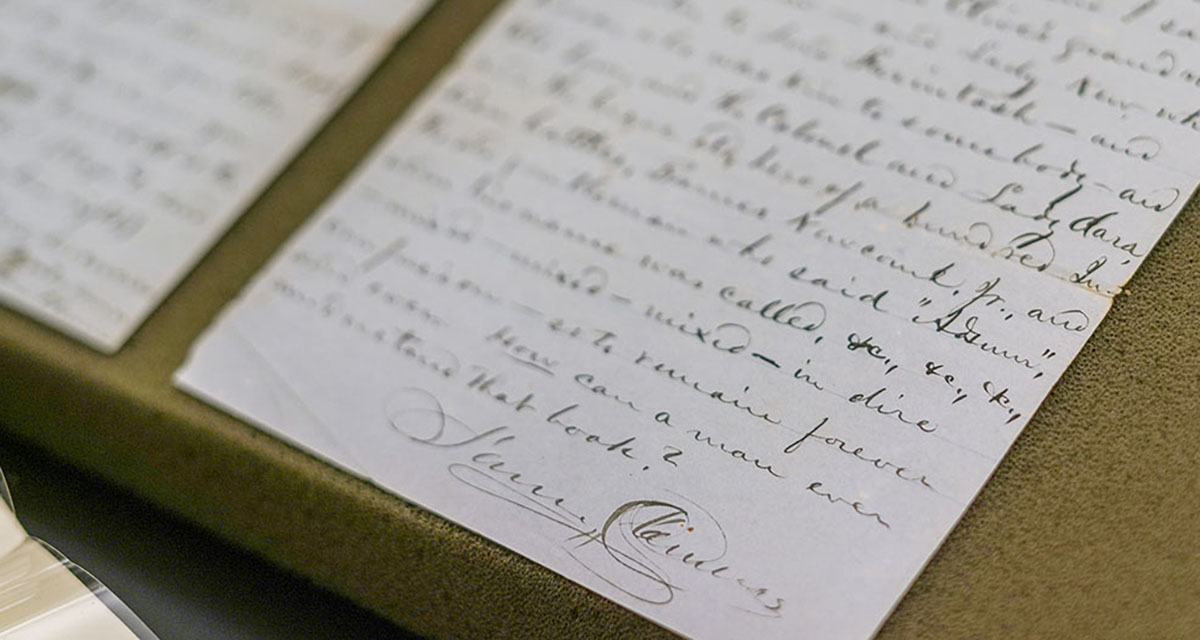

The Bancroft Library’s Mark Twain Papers & Project this month acquired a letter, dated January 1861, that illuminates the least-known period in the author’s otherwise well-documented life. The five-page missive from the then-25-year-old steamboat pilot named Samuel Langhorne Clemens is the oldest known letter Twain wrote to someone outside of his family.

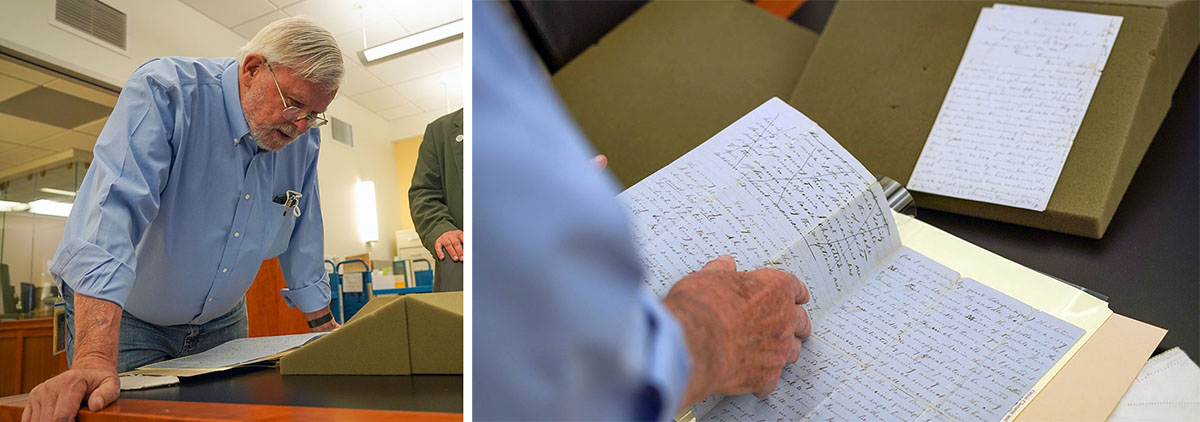

The acquisition is “astonishing” to Benjamin Griffin, associate editor of the Mark Twain Papers & Project (MTP). And that’s saying something: Griffin has spent the better part of two decades painstakingly piecing together Twain’s life amid the world’s largest collection of the author’s private writings and manuscripts.

“Just to learn the letter existed was something of an earthquake here,” Griffin said. “To me, it suggests new avenues of understanding Mark Twain at a whole new moment, on the eve of the Civil War.”

Scholars estimate that Twain wrote at least 50,000 letters in his lifetime, making him one of the most prolific letter writers in American history. Yet this particular artifact stands apart because it was penned to a person previously unknown to Twain scholars — George Beaman, a journalist and friend living in St. Louis.

The contents not only give readers a sense of place and time — New Orleans the day after Louisiana seceded from the Union and just four months before the Civil War — but also make clear Twain’s literary genius well before he became a professional writer.

“Twain claimed that he only got into writing because the war disrupted Mississippi River traffic,” Griffin said. “But this is not the letter of a steamboat pilot; it’s the letter of someone with a vocation for writing that he is already exercising, and you can see him already nearly becoming a master of comic prose.

“That’s something you could never anticipate based upon how the author describes himself when looking back at that period.”

A treasure not lost to time

Griffin and the MTP team first learned about the letter two years ago, when Beaman’s descendants sought out an autograph dealer to help verify the document’s authenticity. The dealer contacted the MTP looking for assurance it wasn’t a forgery and sent four of the five pages to be examined.

“We were excitedly passing around the images, arguing over things like the shape of J’s,” Griffin recalled. “The handwriting is a little different than we’re used to, but we don’t have many manuscripts from him in this period.”

In the end, the team felt confident it was original, based on Twain’s characteristic linguistic flourishes.

The letter is “literary, humorous, Dickensian in some ways, written in a very excited stop-and-start voice, with almost a drunkenness, either real or fictional, being implied,” Griffin said. Twain seems to casually mimic the feel of newswriting, Griffin added, which foreshadows his later work as a journalist, and he’s able to describe with uncanny precision the mood in the hotel where he’s writing from and the family he’s staying with, down to the way they speak.

“You’d have to be supernatural to fake it,” Griffin said.

Authenticating the letter, however, didn’t mean it would end up in the collection, said Bob Hirst, general editor of the MTP. The last time the team purchased an original manuscript of this caliber was a decade ago. But when this unique piece went up for auction in September, the team decided to bid.

“For me, the important thing is that the letter goes somewhere accessible,” said Hirst, who has been a key member of the MTP since 1967. “If another institution gets it, that’s not a disappointment. The danger would be if a private collector bought it and it disappeared.”

The MTP’s goal, Hirst said, is to preserve Twain’s work so everyone can access it. And he credits The Bancroft Library’s generous donors for understanding and supporting that essential mission. In this case, Lorraine Parmer ’50 and her family funded the entire purchase price.

“We couldn’t do this work without the support of our donors,” said Charles Faulhaber, Bancroft’s interim director, “especially at a time when state funding is at an all-time low.”

In his own words

The letter arrived on the Berkeley campus Oct. 1. The blue-tinted, rule-lined manuscript joins a cache of 3,000 letters penned by Twain and an additional 17,000 written to him or his family. Among the author’s many correspondents were historical figures Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, and P.T. Barnum.

And yet Griffin called the letter to Beaman a “jewel in the crown” for the archive because it “peels away so much of the mythmaking Twain did about his own life, and we get an actual look, a real document, from a time we know relatively little about.”

This glimpse into the author’s mind will help Griffin and his colleagues further piece together Twain’s days. The letter also sent Griffin searching for more on Beaman, who, it turns out, lived an extraordinary life. He was a journalist for the Missouri Democrat who was embedded with the armies of Union Gens. Ulysses S. Grant and John C. Frémont. He saw and reported on major Civil War battles.

“This is a letter I never expected to see,” Griffin said. “And it shows us that all fields of study — even those of long-dead American authors — continue to advance. As scholars, we might come to a point where we feel like we know as much as possible, but there is always more to find.”