The UC Berkeley Library is full of stories — and not just the ones that line its shelves. The facts you’ll find here are at turns dramatic, surprising, intriguing, and just plain bizarre, with topics ranging from a double-take-inducing architectural anomaly to a culture-defining concoction. (Hint: The latter one involves a Grateful Dead sound engineer.) If the knowledge you gain here doesn’t pierce the veil of what you thought the Library was, we hope it will at least spark a conversation — or seven. Here are some facts about the Library that you may not know.

1. Humble origins: When instruction first began at the university in 1869, the Library held about 1,000 books, which couldn’t be checked out, and was open for only an hour a day, 4-5 p.m.

2. Inside scoop: The collections of The Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center include the Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream Oral History Project, focusing on the iconic Oakland-based company (which claims Rocky Road among its creamy creations). Interview subjects include John Harrison, the now-retired ice cream tester whose taste buds were reportedly insured for $1 million.

3. Offbeat architecture: Even astute observers may not spot the twist that’s built into the Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library itself. The library’s first floor is aligned with the city of Berkeley’s official street grid, while the top two floors are slightly askew, matching the historic grid of campus. The layout reportedly affords more space at the perimeter of the upper floors for study carrels and seating.

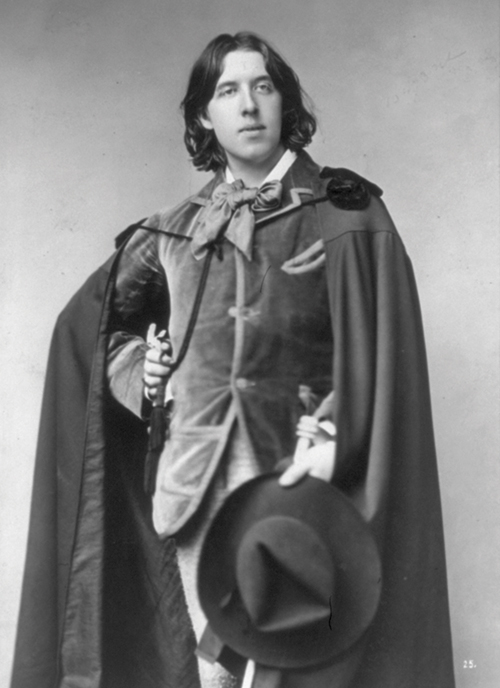

4. Call of the Wilde: In 1882, on a visit to the UC Berkeley campus, Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde toured the Library, then housed in Bacon Hall, drawing a gaggle of onlookers. “We are happy to announce that the students restrained their inherent depravity, and that Mr. Wilde departed uninjured,” the student newspaper reported. Wilde, who was delivering a string of lectures on his Golden State jaunt, was “intensely pleased with the University and was glad to see that the people of California take such an interest in educational matters.”

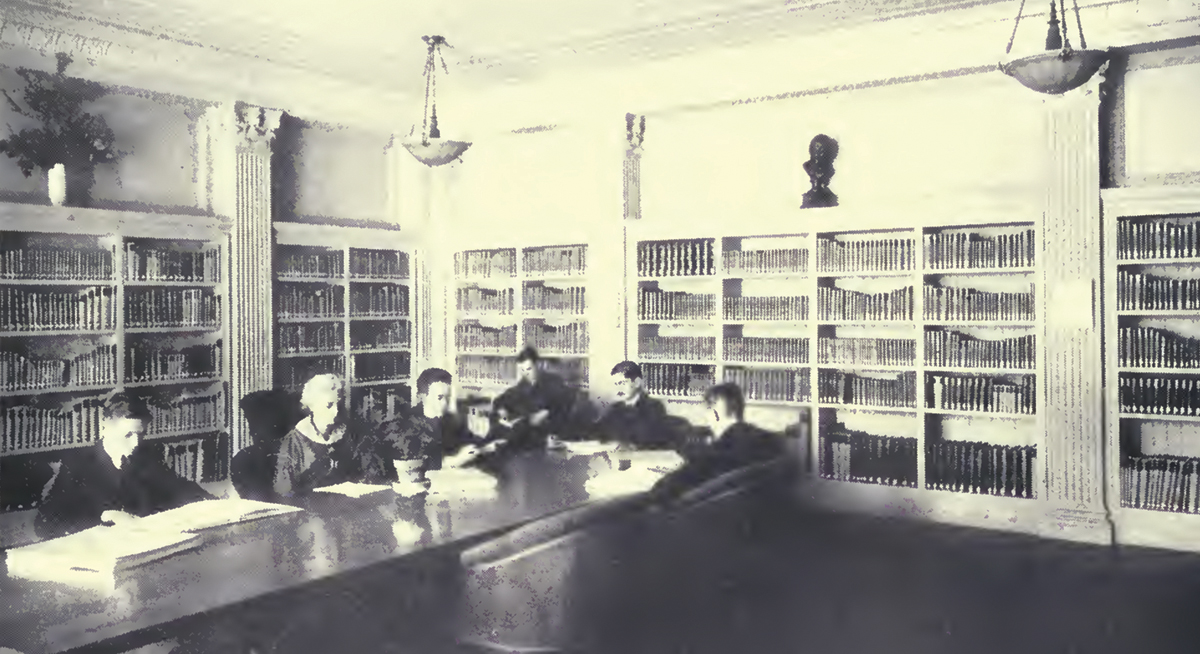

5. Safe harbor: Fearing that the fruits of French thought were in peril during World War I, France’s government sent thousands of volumes to the United States for safekeeping. They eventually were endowed to UC Berkeley, and the Library of French Thought — formerly occupying a room on the third floor of Doe Library — was inaugurated on Sept. 6, 1917.

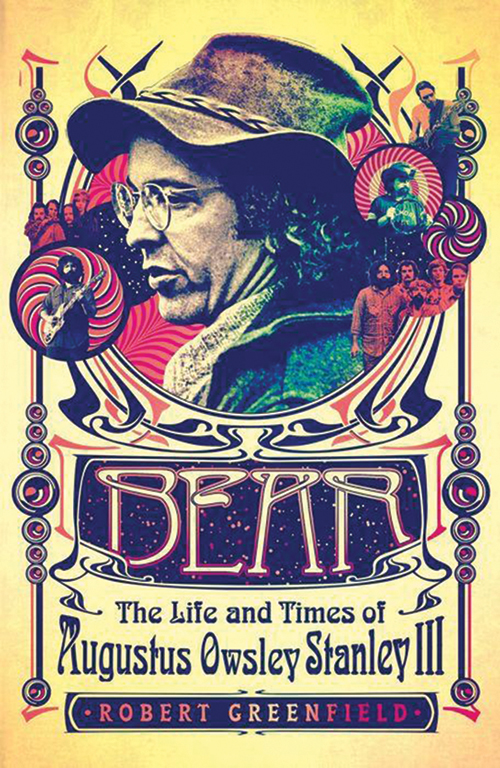

6. The Acid King cometh: After tripping on a particularly potent dose of LSD, Augustus Owsley Stanley III wanted more of the stuff. But he was out of luck. “If I can’t get any, obviously there’s only one other way out,” said Stanley, who had moved to Berkeley in 1964 to take classes at Cal. “Go to the library.” He reportedly spent a couple of weeks poring over the existing literature on lysergic acid diethylamide at the Library in preparation for synthesizing his own supply of the psychedelic. His brain-bending batches would become famous, helping fuel the countercultural revolution of the 1960s. As the story goes, Stanley went on to make more than a million doses of acid, which found their way to the likes of Jimi Hendrix and members of the Beatles and the Grateful Dead (for whom he served as sound engineer).

7. Things we (almost) lost in the fire: The 1906 earthquake and fire rocked the Bay Area to its core, resulting in untold devastation. It also threatened the existence of Doe Library as we know it, years before it opened its doors. On the morning of the blaze, with the San Francisco building that housed architect John Galen Howard’s office condemned, daring draftsman Henry A. Boese jumped into action. He pushed past police lines, climbing six floors of the Montgomery Street building to save the plans for Doe, along with other prized documents.