Cathy Cade first witnessed the power of photography during the civil rights movement, as black-and-white portraits of oppression and resistance blazed across the nation.

It was 1962, and Cade was a visiting student at Spelman College, a historically black women’s school. She was working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a major civil rights organization, in its Atlanta office. The space had a photo lab, where big-name photographers would bustle in and out.

“Danny Lyon (a noted civil rights photographer) would come running out of the darkroom holding up a picture saying, ‘Look at this! Look at this!’” recalled Cade, now 77, from her home in central Berkeley. “A lot of those pictures were used to get support from all over the country. So that was my beginning.

“But I didn’t think I could be a photographer because I was a woman,” Cade said. “That’s what it was like back then.”

In 1969, Cade moved to San Francisco and joined the women’s liberation movement. She surrounded herself with women and learned, among other things, how to tune up her own car — another task women were told they “could never do.”

For Cade, it was a revelation: “I thought, if I can tune up my car, I can take pictures.”

Cade began photographing in 1971 — the same year she came out as a lesbian. In the decades since, Cade has documented the quiet joys and great successes of womenhood, focusing on the lesbian community of the Bay Area. An activist with a camera, she has marched for equality on all fronts, photographing moments ranging from California’s earliest Pride parades to the 2011 Occupy movement.

“She’s all about the power of visibility,” said Christine Hult-Lewis, curatorial assistant for The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. “It’s not only lesbian rights. It’s labor rights, civil rights, feminism as women’s rights — all these different sections that coalesce and converge in the very person of Cathy.”

In 2012, Bancroft acquired Cade’s full photo archive — the library’s only full archive from a lesbian photographer, containing thousands of negatives and Cade’s personal writings. There, Cade hopes her photographs will teach future generations “where we were and what we’ve done.”

In honor of Pride, we asked Cade to reflect on some of her most iconic photographs over the past 50 years. Here’s what she had to say.

Love for the ages

This one is from the 1972 Christopher Street West demonstration in L.A. (The parade, a precursor to Pride, honors the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall riots, when police raided a gay bar on Christopher Street in New York City.) There’s an old white woman carrying a sign that says, “Sisterhood feels good,” and she’s got a big smile on her face, and she’s kind of staring into the eyes of a man who you can only see from the back. So I’m at the parade, and I’m photographing, and I see this woman — in ’72, I was 30 — I see this woman and I go, “Wow, there’s an old woman who’s demonstrating!” That was such a big piece of news to me. She was probably my mother’s age … and she was out, being public about being a lesbian. There were older lesbians, but they weren’t out — they felt much more vulnerable, which they were, in lots of ways. The boldness of being out, publicly out, as a lesbian, at her age — I went, “Wow.”

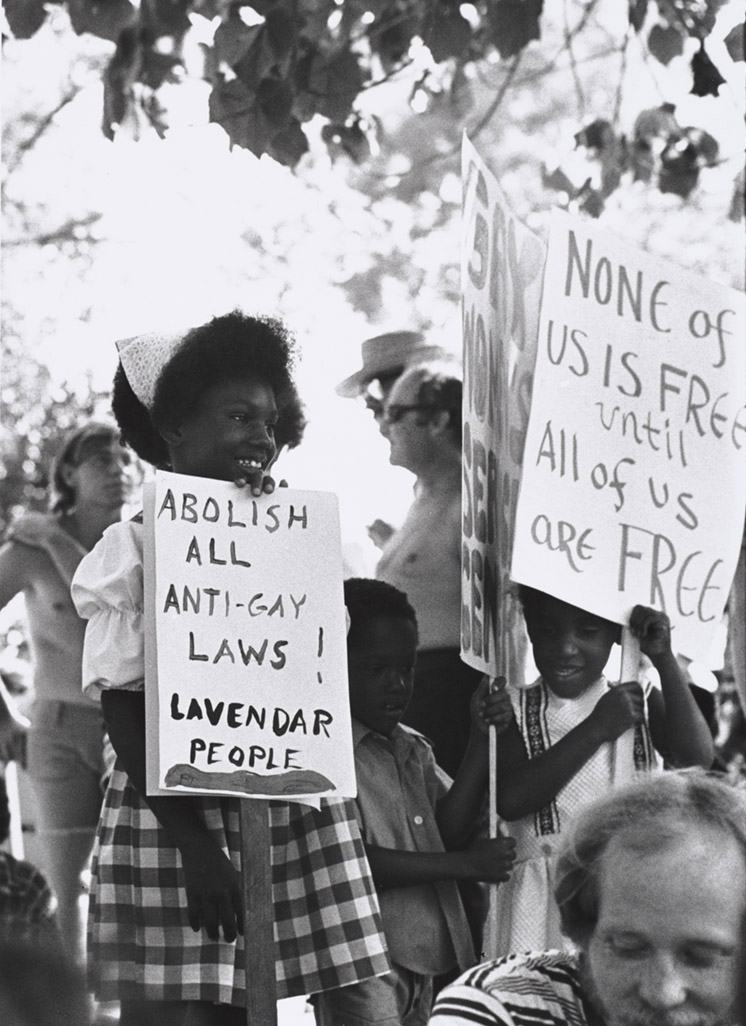

‘The movement is moving on’

These demonstration pictures show a person with a sign that has a statement, and that combination was very powerful. You don’t know what a person is thinking when you see them — you can look at them and have ideas about what they represent and who they are, but it’s limited. And when you have a sign, that’s another chunk of information. … So here’s a young girl, you would look at her and think she’s a black person. But she’s saying, I may be black, but I’m supporting all of us lavender people. (Before the rainbow flag, lavender was associated with the LGBTQ community as a symbol of the blending of the gendered colors pink and blue.) I said, look at this, the movement is moving on! It was about civil rights for black people, and now it’s civil rights for black gay people. And it’s a young generation — these are kids. This one girl is probably 10, and next to her is probably a 5-year-old and a 7-year-old. And they’re all for it — let’s go! They’re obviously having a lot of fun.

Women in the workforce

This is a picture of Kate, who is working on repairing the engine inside an East Bay (Municipal Utility District) truck. And that’s her job! She had a job working for East Bay MUD! First of all, she learned the skills to be able to apply for the job. And they hired her. We called them “nontraditional” jobs. There were women who were becoming auto mechanics and carpenters and learning all these skills and having all these jobs that we had been raised to think was impossible. And this was very exciting to all of us. Whether that’s the road that you were taking or not, it was very exciting that women were able to learn the skills and get the jobs.

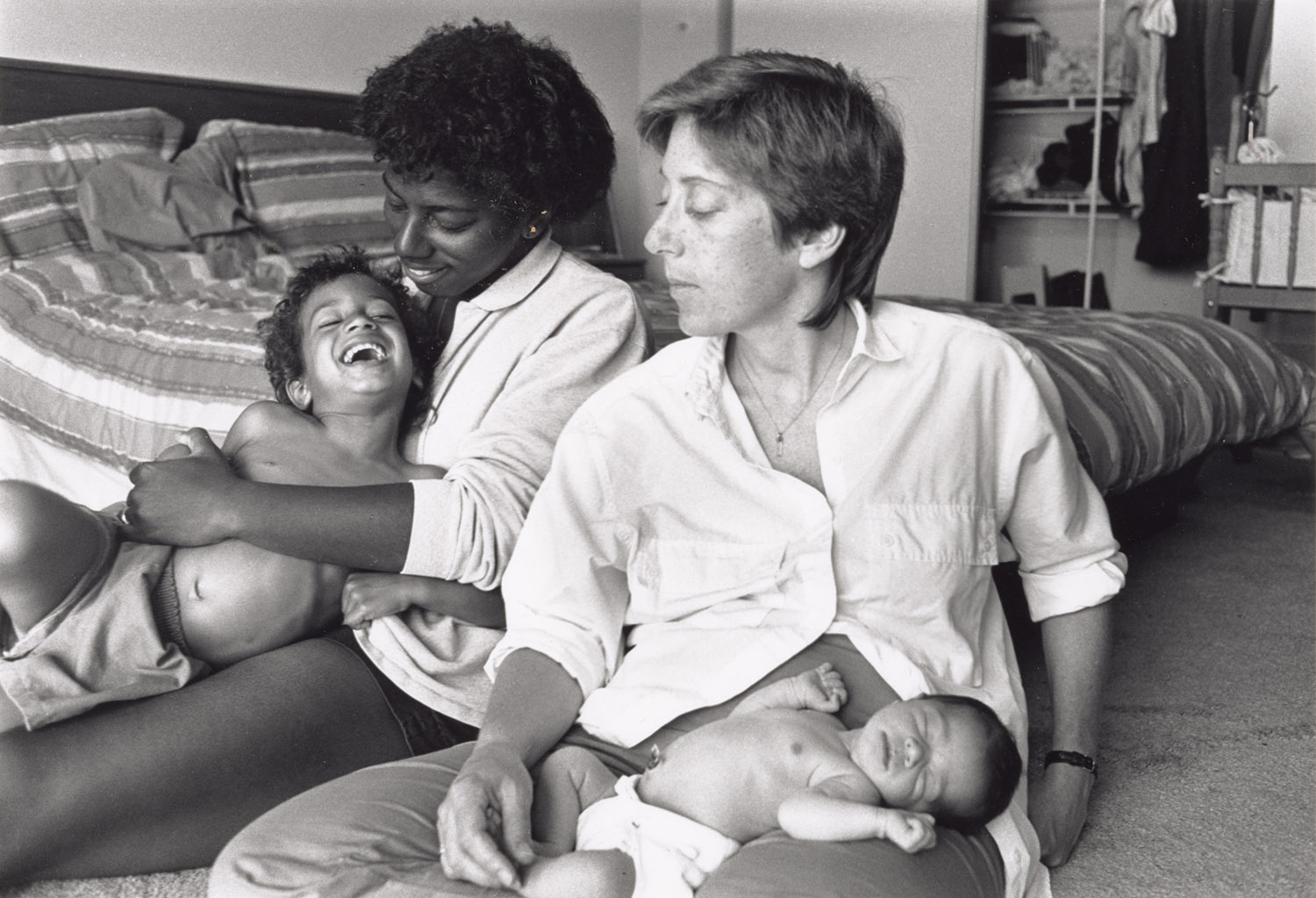

Motherly pride

When I lived with Kate (Cade’s former lover, seen in the previous photo), I became a part of a lesbian mother support group. It was a time when, OK, we can claim being women who have skills, we can claim being lesbians, and, my God, we can go on and claim being mothers as lesbians. We had support groups where lesbian mothers around Berkeley and Oakland got together and, every other week, we talked about what was happening for us as a lesbian mother, or being in a relationship with one. We talked about what it was like taking your kid to school and what the teachers were saying. It was very important to have a place where you could … learn that there are other people having similar problems or successes. That we weren’t the only one. That was very empowering. Photography was another way. People who saw the pictures could have some of that same benefit. They could say, “Oh look, here’s another lesbian mother.”

All in, all out

Here’s a crowd — this is a large number of women — and it’s all women. To have a group of demonstrators that was all women, that was new and radical. And to have them look so happy! They’re not being scared, they are totally celebrating, and they are totally out. One sign on the left takes the phrase “Sisterhood is powerful,” which came from the feminist women’s movement, and added on top that gay sisterhood is powerful. So they’re saying, OK, we’re feminists, but a particular kind of feminists. And then the big middle banner says “Gay is good.” Well! Who knew that gay was good? In the ’60s! That was not a combination of words that anybody had thought of. It’s not that it’s OK to be gay; it’s like, gay is good.

Then there’s a banner with a women’s symbol, with a peace sign in it. And that was a whole other part of the politics. Feminists were against the war in Vietnam. So there’s a lot going on there. And it just so happens that they’re marching in front of a Shell station. I don’t know if we were demonstrating against Shell Oil yet — that probably came later.

Photos: [Cathy Cade photograph archive], BANC PIC 2012.054. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.