They went into the ground, together: ancient texts and artifacts, two halves of a story more than 3,000 years old.

And now, in the soft-lit gallery of The Bancroft Library, they are together once more.

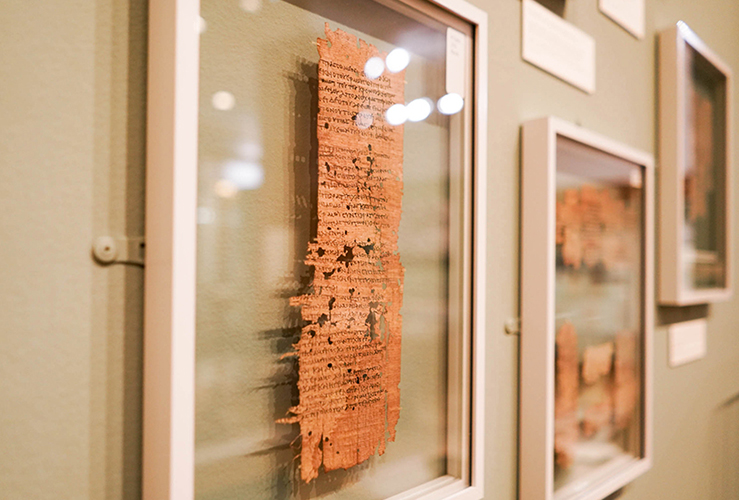

A new exhibit, Object Lessons: The Egyptian Collections of the University of California, Berkeley joins papyrus texts from the library’s Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, or CTP, with ancient objects from UC Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology — including a 4,000-year-old statue from the Great Pyramids of Giza, papyrus fragments from Sophocles’ lost play Inachus, and an 8-foot mummified crocodile from a reptilian god’s temple. Side by side, the materials cast color and context upon each other, offering a wider, brighter peek into life in antiquity.

It is the first time these historic collections have been reunited on such a grand scale since they came out of the ground.

“Scholars have tended to look at (papyri) as just words on a page, completely removed from the society that read them, that used them, and for which they were real,” said Todd Hickey, head of CTP (which holds one of the foremost collections of Egyptian papyri in the world). “We wanted to bring out in this exhibit the fact that, no, these things were objects, and they existed alongside other objects.”

“The context of these papyri matters,” he added. “The history of the object over time matters.”

Object Lessons: The Egyptian Collections of the University of California, Berkeley

Where: The Bancroft Gallery and second-floor corridor, in Doe Annex

When: Object Lessons opened Oct. 14 and runs through May 22, 2020, with several items to be swapped out in February; the gallery is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Cost: Free

A window into antiquity

In the ancient town of Tebtunis — what is now Umm el-Baragat — papyrus plants flourished in the fertile Fayum basin just west of the Nile River. Their stems, peeled into strips and layered like Jenga blocks, were pressed into papyri, paper’s earliest ancestor, and used to record everything from the whims of village life to performances of epic poems.

But the texts also had an afterlife: They helped preserve the bodies of the dead — either stuffed into the inside or wrapped and plastered like papier-mâché.

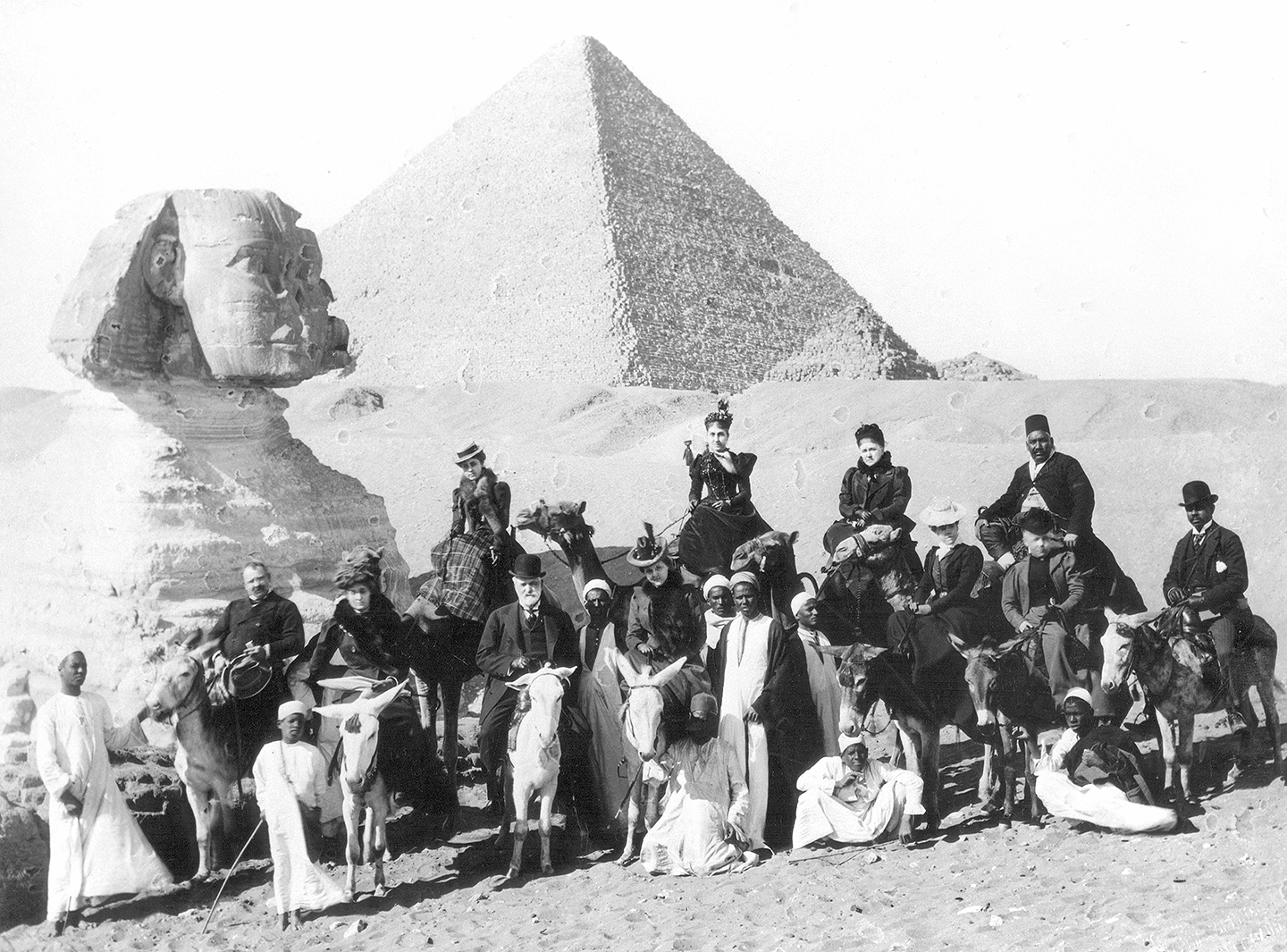

The vast majority of the papyri in CTP’s collection come from the towns and cemeteries of Tebtunis, dug up by British papyrologists Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt during the winter of 1899-1900. The excavation, funded by famed University of California benefactor Phoebe A. Hearst and led by Egyptologist George A. Reisner, yielded an astonishing 26,000 pieces of papyri and other objects.

Reisner continued to work for Hearst for several years, leading excavations across Egypt. Through Hearst’s philanthropy, CTP’s collection of papyri, mostly from the Greco-Roman period, is one of the largest in the world.

Among the rare papyrus texts now on display are an account of the Trojan War attributed to the soldier Dictys of Crete, in the original Greek; a nearly 2,000-year-old copy of Homer’s Iliad, paired with audio from a graduate student’s reading of the tale; and administrative accounts of Middle Kingdom Egypt from the site of Naga ed-Deir, in the southern part of Egypt, written in a cursive hieroglyph script and dating back some 4,000 years.

Right next to those stars are the splendidly mundane: receipts for land, letters to family, and other souvenirs of day-to-day life.

“Anytime we find a new document, people say, ‘Oh, we found another lease for land, big deal,’” Hickey said. “But all these documents accrue and build up and allow us to write the kind of history that you can’t write anywhere else in the ancient world — certainly not with the richness that we can with Egypt.”

For Andrew Hogan, a lead curator of the exhibit and postdoctoral fellow at CTP, those fragments fill in the small but crucial gaps in history, adding new texture to the tapestry of humanity.

“That’s what I love — the notion that we can actually see business practices, religious practices, mortuary practices,” Hogan said. “It does tell us, within context, where we come from.”

The circuitous journey

A second part of the exhibit tracks the papyri’s journey from Egypt to Berkeley.

Some of the papyri excavated by Grenfell and Hunt in Tebtunis were sent to the University of Oxford for further study. Those texts began to arrive in Berkeley in the late 1930s.

But Reisner, the German archaeologist who led other UC excavations at the Great Pyramids of Giza and Naga ed-Deir, sent the papyri he found to Berlin for conservation.

From there, the papyri were: hidden from Soviet officials at the end of World War II; moved into houses and shops across West Berlin; shipped from Switzerland; and taken to Boston by a scholar who lied to UC researchers about the papyri’s whereabouts. The items stayed in Boston, at the Museum of Fine Arts, until 2006, when their intended destination was revealed.

The goal, said Emily Cole — also a lead curator of the exhibit and postdoctoral fellow at CTP — was to tell both sides of the papyri’s story, ancient and modern.

“It adds this extra layer — look at the lengths people go to move the papyri around and preserve them,” Cole said. “There are all of these different contexts one step after the other — another person being influenced, and another.

“A person walking into the gallery is going to have a whole new experience with these objects and their stories.”

A global education

The hope, curators said, is to share that experience as widely as possible.

The exhibit team is currently working with the Hearst Museum to bring K-12 students from across the Bay Area to the show. (Bancroft will also be sponsoring field trips for some students.) Together with the museum, curators have also created an interactive museum guide, primarily aimed at sixth graders, with various exercises.

“For me, the draw of the exhibit is the ability to be an educator,” Hogan said. “This is an amazing research post, but it allows us to feed our soul on the other side, to think about: How is a sixth grader going to take this? How is a Cal undergrad going to approach this?”

(Cole and Hogan spent a year working with the collections and conceiving the exhibit. Hickey, smiling at his mentees across the table, said he mostly “stood back and watched them work.”)

In fact, two core tenets of CTP’s mission are education and access. The center lets graduate students and undergrads work with papyri hands-on, and puts on classes, workshops, and seminars throughout the year.

The center also opens its collections to researchers around the globe. It provides high-resolution images of unpublished papyri to outside scholars upon request and has made thousands of unedited pieces available through its website and papyri.info.

That’s partly out of necessity, Hickey said. Around 90 percent of CTP’s monumental collection of papyri remains unstudied, with countless secrets about ancient Egypt left to discover.

“At the present rate, the sun is going to die before we’re done with our papyri,” Hickey said. “This isn’t a one-person job, or a three-person job. This is a job for the world.”

This article has been revised to remove references to Berkeley as the papyri's home. We regret this mischaracterization.