The building and its origins

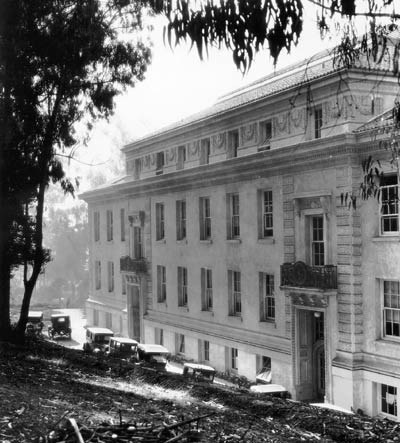

Haviland Hall was completed in 1924, one of a collection of buildings by campus architect John Galen Howard (1864-1931) that transformed the Berkeley campus.

Inspired by California’s growing importance, and with the backing of Phoebe Apperson Hearst, a major benefactor of the early university, the university launched an international competition in 1898-99 for master plans for the development of the campus. French architect Emile Bernard won the competition -- Howard placed fourth -- but differences with Bernard led to his departure in 1900, and Howard was appointed as supervising architect in 1901.

Howard's designs reflect his training at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Although originally appointed to implement Bernard’s plan, Howard reshaped it into his own, developing a "City of Learning" that turned the central axis of the campus back toward the Golden Gate, as originally envisioned by Frederick Law Olmsted's 1865 campus plan. Among the campus landmarks built during his tenure were the Hearst Memorial Mining Building (1902-7), the Hearst Greek Theatre (1903), California Hall (1905), Doe Library (1911-17), Sather Gate (1910), Durant Hall (1912), Wellman (formerly Agriculture) Hall (1912), the Campanile (1914), Wheeler Hall (1917), Gilman Hall (1917), and Hilgard Hall (1918).

Haviland Hall was one of the final buildings of the Howard era. It bears an uncanny resemblance to a design for new North Hall on the site of an earlier North Hall, just east of Doe Library, which had been demolished in 1916. Haviland Hall was conceived in its present location as a symmetrical balance to California Hall across the central axis of the campus, in accordance with Howard's master plan for the campus.

Haviland Hall is named after Hannah N. Haviland, wife of John T. Haviland, a San Francisco banker. Her sister was the first wife of industrialist Collis P. Huntington. Upon her death in 1919 at the age of 94, she bequeathed $250,000 to Berkeley for the construction of the building. (Perhaps foreshadowing the building's eventual home for the School of Social Welfare, Haviland also left $20,000 to the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum.) In 1921, the California legislature contributed an additional $100,000. Haviland Hall was built specifically to house the School of Education and Lange Library of Education, which occupied the building from 1924 to 1963.

The newly constructed Haviland Hall, c. 1924

The building was formally dedicated on March 25, 1924, in a ceremony featuring a speech by Dr. WW Campbell, president of the University of California, and appearances by the dean of the School of Education, the Oakland superintendant of schools, the state superintendant of public instruction, and other notables. The program included an exhibition of work of the Berkeley public schools in the 3rd floor exhibition room and an informal talk on "Haviland Hall as a clearing house for educators."

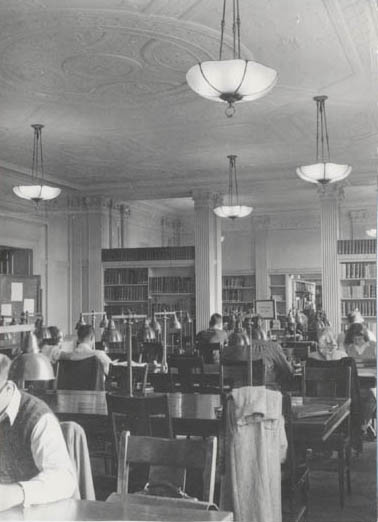

The building is ornamented with details relating to its original purpose. Open books and medallions of Pegasus, regarded as the horse of the Muses, decorate the exterior. The neoclassical reading room was done in the "Adams Style," after Robert Adams, 18th-century Scottish architect.

Haviland Hall was designated a City of Berkeley Landmark in 1981. In 1982, it was also added to the National Register of Historic Places (#82002161).

Social Research Library

Until 1961, the Lange Education Library occupied the site of the present Social Research Library.

Lange Education Library reading room, 1950s; view from the rear of the reading room.

Reading room looking toward site of present circulation desk

Looking into the seminar room.

Detail of lamps and ceiling

The Social Research Library was originally established in 1957 as the Social Welfare Library, a unit of the Social Sciences Library, and was located in Stephens Hall where the Ethnic Studies Library is currently situated.

Upon relocation of the School of Education to Tolman Hall in 1963, the chambers at either end of the reading room were walled off, as was the main second-floor corridor. The library was installed in the spaces currently occupied by rooms 215-218. Emptied of books, cavernous, and lit by graceless fluorescent lights that replaced the Beaux Arts originals, the reading room became little more than a passageway through the building.

Studying in the vacant reading room, c. 1980

(Photo by Lora Graham)

The reading room languished until 1986, when a major renovation led by the School of Social Welfare restored the space. The reading room now "is among the significant remaining interiors of Howard's campus buildings." (University of California, Berkeley : an architectural tour and photographs. Harvey Helfand. New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.)

In 2014, the library was renovated, its facilities were upgraded for the 21st century, and its focus was broadened to become the Social Research Library.

School of Social Welfare

The School of Social Welfare took up residence in Haviland Hall in 1963 after almost twenty years in makeshift campus buildings. Although the School was formally organized in 1944, a social welfare certificate program began in the 1920s, and antecedents of the social welfare curricula stretch back to 1904, when economics professor Jessica Peixotto first began teaching courses in social welfare. A comprehensive history of the School was published on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in Social Welfare at Berkeley, v.6:1 (fall 1994), HV11.C322.

Architectural hairnets

Visitors to Haviland sometimes remark on the netting installed over the decorative details -- quoins, bas reliefs, and cornices -- on the exterior of the building. An analysis in 2004 revealed that chemical changes in the cast stone was causing the underlying steel reinforcing bars to corrode. Corrosion caused them to expand, cracking and spalling the concrete and causing it to come loose. Netting was installed for the safety of pedestrians, pending repair. Renovation will require new molds and castings of the ornaments, at an estimated cost of at least $2 million.

Rockin' and rollin'

For years, Haviland Hall has been used as a seismic recording station. Buried deep in Haviland's subbasement, nestled into the Franciscan sandstone, is the station BRK seismograph, part of the Berkeley Digital Seismic Network. You can take a peek at the seismograph recordings of the previous 24 hours for the stations around the state, including Haviland Hall (Station BRK). The entrance to the subbasement seismic station is next to the CSSR office.

Seismographs have been located on the campus since 1887. During the Cold War, the Haviland Hall seismograph played a small part in the nuclear arms race. Nuclear physicist Edward Teller, known as the "father of the hydrogen bomb," recalled descending to the Haviland Hall seismograph in October 1952 to monitor the detonation of the first hydrogen bomb "Mike" on the island of Elugelab in the Eniwetok Atoll, 3,000 miles west of Hawaii. The seismograph rested on a concrete pier, dimly lit by a red lamp:

After my eyes became accustomed to the darkness I noticed that the light spot seemed quite unsteady. Clearly, this was more than what could be due to the continuous trembling of the Earth -- the microseisms . . . So I braced a pencil on a piece of the apparatus and held it close to the luminous point. Now the point seemed steady and I felt as if I had come back to solid ground again. This was about the time of the actual shot . . . About quarter of an hour was required for the shot [waves] to travel from deep under the Pacific basin to the California coast. I waited with little patience, the seismograph making at each minute a clearly visible vibration which served as a time signal. At last the time signal came that had to be followed by the shock from the explosion. There it semeed to be: the luminous point appeared to dance wildly and irregularly. Was it only that the pencil which I held as a marker trembled in my hand? Finally the film was taken off and developed. Then the trace appeared on the photographic plate. It was clear and big and unmistakable. It had been made by the wave of compression that had traveled for thousands of miles and brought the positive assurance that Mike was a success.

(Nuclear explosions and earthquakes: the parted veil, by Bruce A. Bolt. SF : Freeman & Co., 1976)

The enormous blast created a crater more than mile wide, obliterating the island, and marked a major escalation in the nuclear arms race.

Berkeley Conservatory

Nestled against Observatory Hill for 30 years, on the site of what is now the Chang-Lin Tien East Asia Center, was the UC Berkeley conservatory. Built in 1894 by Lord and Burnham, the conservatory was modeled after the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers in Golden Gate Park, which was built by the same firm. It was the result of a 1880s campaign by agriculture professor Eugene Hilgard, who lobbied the Berkeley Regents for the its construction and was closely involved in its planning. Hilgard, regarded as the father of soil science, even traveled to Europe in 1893, delaying work on the project while he inspected prominent conservatories across the continent.

The main part of the conservatory housed palm trees, and the wings included a cellar, potting shed, and a boiler room. It was the centerpiece of a 7-acre university botanical garden, created by the Regents for "a garden distinctively botanical" similar to "a part of the pride of almost every university in Europe at the present time." The conservatory and grounds appear in an 1897 campus plan, and the early garden is visible in an 1899 view from just about where Haviland Hall's southeast corner is today. A 1924 photo shows a fully developed garden. In 1924, as part of the campus's expansion, including the construction of Haviland Hall, the botanical garden was relocated and the conservatory torn down. By 1928, Haviland Hall was alone in this part of campus, with only the Chancellor's house and Observatory Hill as neighbors. Aerial photos from 1928, 1939, 1946, 1956, 1985, and 1994 show that for more than 80 years, Haviland Hall enjoyed solitude among the trees and the creek.

The site of the conservatory eventually became a parking lot. In 2005, in anticipation of the construction of the Tien Center, anthropology students excavated the site. Findings included thermometer fragments, flower pots of various sizes, plant tags, glass droppers, a watch-chain loop, a number of marbles, an antique brass button featuring a bas-relief of Minerva from the Great Seal of California, and a 116-year-old dime, minted just 18 years after the campus opened its doors.