It’s on an otherwise nondescript city block in the East Bay.

After snaking your way through a driveway between two unassuming houses, the Wizard of Oz technicolor kicks in. An ordinary street scene opens onto a symphony of textures and hues. Jackson Pollock splotches of bright orange, purple, red, and yellow float in a sea of green, popping into focus like a Magic Eye.

Each step reveals more untamed beauty. A calico cat lazily saunters by. The sinewy limbs of a fig tree twist every which way. Reeds rise from a creek bed, as if climbing to the sun.

“If you didn’t know what was there, you’d probably walk right past it,” says Seth Lunine, a continuing lecturer in UC Berkeley’s Department of Geography.

Canticle Farm is a hidden half-acre oasis pulsing with life in Oakland’s Fruitvale district — a bounty of flora and fauna living together, embodying a vision of what could be. And with the help of the Earth Sciences & Map Library, the intertwining visions of Canticle Farm and a geography class at UC Berkeley have provided students with an opportunity for hands-on learning about injustice, the power of place, and the hidden world in our own backyard.

More than maps

The idea for the project emerged in an unlikely setting.

Robert Symens-Bucher ’22, whose parents started Canticle Farm about a decade ago, had invited his instructor to a party to celebrate his graduation and birthday. Lunine showed up, and the two got to talking.

“It was like, ‘How can we help you? How can you help us?’” recalls Symens-Bucher, who graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in human geography. “How can we do this thing together? Because there’s a lot of potential for good stuff to happen here.”

Canticle Farm is more of a secret garden than the typical farm that you might conjure up in your head. You won’t find a barn, chickens, mass-market monocrops, or so much as a spray of pesticide here. Instead, you’ll find a vibrant community — a cluster of homes, all sharing the same verdant backyard — with a purpose-driven mission.

The name “Canticle Farm” itself is a bit of a misnomer, Symens-Bucher says. Sure, there are herbs, fruits, and vegetables — but its aim goes far beyond the plants that cover its lush landscape. Its moniker comes from the story of St. Francis of Assisi. Born into a wealthy family in 12th-century Italy, Francis went on to refuse his inheritance and turn to a simple life committed to serving others. Late in his life, close to death and nearly blind, he wrote a canticle, or song, rejoicing in the beauty of the world, and kinship with all creation — a philosophy that Canticle Farm embraces with open arms. (Its motto? “One heart, one home, one block at a time.”)

“It’s about living across difference,” says Symens-Bucher, a fifth-generation Fruitvale district resident whose parents have lived on the site for four decades. “It’s about being in service to the community.”

Life abounds in the garden, which is home to salamanders, skunks, prickly pears, plums, medicinal herbs, hummingbirds, bees, raccoons, frogs, and other plants and animals, big and small. Through its programs, Canticle Farm offers shelter and support to formerly incarcerated men of color paroled from life sentences; asylum-seekers; and youth activists taking up the mantle of climate, housing, and food justice, and Indigenous sovereignty.

“What’s amazing about (Canticle Farm) is that they are, on a micro scale, demonstrating and elaborating solutions and approaches to a lot of our biggest challenges,” Lunine says.

In the fall of 2022, the idea that was planted during the conversation between Symens-Bucher and Lunine began to take root. A group of students in Lunine’s Geography 50AC class, which traces the spatial history of California, signed up for the Canticle Farm project, part of the American Cultures Engaged Scholarship, or ACES, Program.

Over three semesters, dozens of first- and second-year students have worked on the project of untangling the messy history of the site that Canticle Farm sits upon, with Symens-Bucher serving as a liaison between the garden and the students. The project was designed not only to deepen the collective understanding of the land, but to provide students with firsthand research experience and an up-close look, beyond the walls of a classroom, at injustice in the world — and ways to help.

To start, students turned to maps and readings from class, and began scouring the internet, but that took them only so far.

“The Earth Sciences & Map Library was on our radar from the beginning,” Lunine says. “But it became much more imperative because we needed to get our hands dirty by sifting through the incredible repository there.”

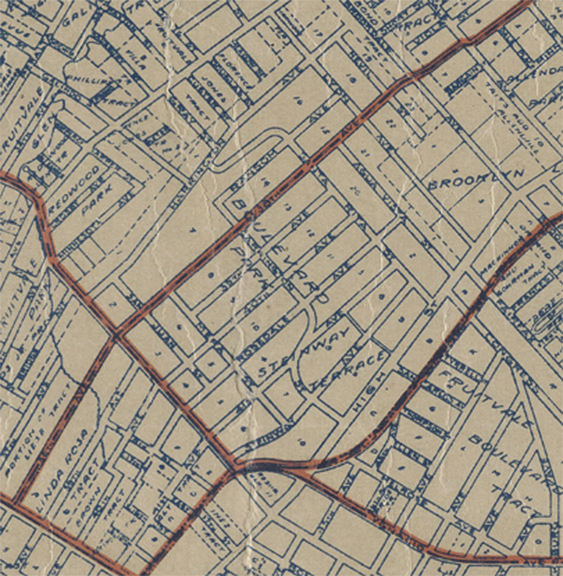

Susan Powell, UC Berkeley’s geographic information systems and map librarian, and Heiko Mühr, Berkeley’s map metadata and curatorial specialist, showed students new tricks for finding the right sources, and introduced them to some of the materials from the Earth Sciences & Map Library. The library’s collection of oversize rolled maps provided students with a close-up look at change in the East Bay, including the historical names of communities and neighborhoods.

One of the early breakthroughs came courtesy of the library. A large wall map located by library staff, issued in 1914 by an Oakland-based real estate development firm, revealed the onetime name of the tract that Canticle Farm straddles: Boulevard Park. With this discovery, students were able to locate a tract book — a ledger with detailed information about the area’s land parcels and historical ownership.

“It was serendipitous and dependent upon the knowledge and expertise of the folks in the library,” Lunine says. The map has since been digitized by the UC Berkeley Library’s Imaging Services team and uploaded to the Library’s Digital Collections portal, where it is now freely available to everyone.

The information “was like a puzzle piece,” Powell says. It unlocked new possibilities, sending students deeper into their research journey, which took them to The Bancroft Library, the Oakland Public Library’s Oakland History Center, and across the internet. For the project, Lunine and the students also have enlisted the help of others, including experts in history, archaeology, and integrative biology.

Among the most exciting discoveries the students made came from a 2006 archeological report, which revealed that grinding stones had been found on the site. The stones themselves are no longer there — they were removed and likely fell into the hands of a collector — but their onetime presence provides insights into the site’s Indigenous inhabitants before colonization, and its historical ecology. A grinding stone is a slab of rock that works like a mortar, used to break down acorns and other plant material before they are eaten. In preparing acorns for consumption, water was used to drain them of bitter tannins. The existence of grinding stones suggests that the creek that cuts through Canticle Farm, which now flows only in the winter and early spring, was once a more reliable water source. This could mean that a seasonal, or even year-round, village once sat on the site, Symens-Bucher says.

As part of the project, Ally Matheson ’26, who’s pursuing a major in geography and a minor in human rights, looked into the history of the grinding stones, as well as the legacy of dispossession in the area. Drawing upon what she learned in Lunine’s course, as well as online sources and materials from the map library, Matheson examined the connections between redlining — the discriminatory lending practice that deprives resources from people living in certain areas — and gentrification — the displacement of those very people by transplants with more material wealth.

“These are patterns and processes of exclusion — of land taking, of extracting value,” Lunine says. “We want to think critically about the ways in which the history of the site … shapes what’s going on today.”

Erendida Corona ’26, a math major, was part of a research team looking into the precolonial ecology of the area. She remembers visiting the map library one day, looking for sources. Powell provided tips on searching for materials, and found a map that Corona ended up using for the project.

Through the Creeks of UC Berkeley website, Corona got a sense of the historical plant life along Strawberry Creek, which meanders through campus. The resource provided clues about what the native vegetation around the creek at Canticle Farm might have looked like, given the proximity.

For Corona, the project shined light on the power and versatility of maps, and the subtle and not-so-subtle messages they can convey. The information embedded in many maps, like ones she explored for the project, are filtered through the perspective of colonizers, and omit generations’ worth of knowledge of Indigenous people, she notes. The project also challenged assumptions about what a map is. Maps don’t have to be ink on paper. Students learned, for example, about an Indigenous group’s use of carved wooden maps. Because of their form, the maps could withstand harsh conditions and could be used even in the dark of night.

Before taking Lunine’s Geography 50AC class, Corona didn’t have much familiarity with the field. But the experience inspired her to declare a minor in geography.

“When I thought of geography, I thought of locations on a map,” Corona says. “But there’s just a lot more to it.”

‘Not a typical research project’

As part of the project, students are working on a documentary about Canticle Farm, in collaboration with Restorative Media, a nonprofit. They’re also developing a public-facing website, where anyone will be able to learn the fascinating and complicated story of the land, interwoven with the stories of genocide, land theft, and ecological crisis. This will also help contextualize Canticle Farm’s ongoing programs supporting Indigenous activism, formerly incarcerated men, asylum-seekers, and ecological remediation.

“We hope the website will help with processes of not only acknowledgement, … but also healing,” Lunine says.

The Canticle Farm project is “not a typical research project,” for students and for Library staff, Powell, the map librarian, says. The endeavor allows students to work closely with primary documents, which doesn’t happen often enough so early in the undergraduate experience. It also offers the chance for students to become more comfortable with the research process, and the discoveries and disappointments along the way.

“It’s really an open-ended inquiry,” she says. “And that was nice for us as librarians, to help them navigate the different conduits of research … and have the research process just be transparent and messy — which it is.”

Working directly with Canticle Farm adds another important dimension. During the course of the project, students get to visit the site together. There, they present what they’ve learned, and share meals and conversation with members of the community. (They also presented their findings at a pop-up exhibit in the Earth Sciences & Map Library.)

“It wasn’t like they were just researching this term paper about some abstract topic,” Powell says. “They had seen the place, they met the people — and so that helped make the connection to the sources really powerful for them.”

The project has not only opened students’ eyes to the past and present of the Bay Area, a new environment for many of them — it has also imparted unexpected life lessons. For Matheson, it was a “reality check.”

“I’m learning about human rights (in class),” she says. “I have flash cards and stuff, but it’s not the same as actually sitting down with people who are trying to get asylum in the U.S. or people who have experienced incarceration. …

“I think one of the biggest things I gained from this was I got much better at listening.”

Lunine has opened the project up as much as possible to anyone in his class who is excited about it, in a conscious departure from the competitive and, at times, stressful nature of clubs and research opportunities that proliferate at Berkeley. The project has attracted students from a broad range of disciplines — math, music, political science, psychology, business, theater, and geography, to name a few — and from across the state, country, and world — including international students from Kuwait and Iran.

Throughout the project, Lunine has cultivated a welcoming, supportive environment for everyone who takes part, including first-generation students and students from historically marginalized communities. Lunine, who earned his bachelor’s degree and Ph.D. at Berkeley, knows how overwhelming the university can be for a student.

“For them to find their voice, to feel comfortable, to find a place, even if it’s somewhat ephemeral, to engage — for me, that’s one of the most meaningful elements,” he says.

By shaking students loose from the predictable pattern of a typical classroom experience, the Canticle Farm project gets them in touch with a deeper purpose, Lunine says.

“I see students … just really running with this research,” he says. “Once we move out of the mode that we’re all used to — of thinking about how to get an A-plus — once we start working on behalf of people or issues other than or larger than ourselves, there’s incredible excitement.”