Do you savor the splendors of living near the San Francisco Bay — the sweeping views, the bounty of wildlife, and the tranquil walks along its tidal wetlands?

If the answer is “yes” — and why on earth wouldn’t it be? — you have activists to thank.

By the 1960s, the future of the bay was grim. To meet the needs of a proliferating population, surrounding cities had planned to push their boundaries off the edge of the continent, turning the bay into a paved paradise and shrinking the beloved body of water down to the size of a wide river. In Berkeley, swelling city limits would have doubled the town’s size.

In 1961, an article in the Oakland Tribune, accompanied by a map from the Army Corps of Engineers, sounded the alarm on this fate, which the bay was projected to befall by the year 2020.

But the environmental movement, and the everyday people at its heart, turned the tide, staving off this alternate-universe reality before it started.

This sliding-doors saga and other stories, told by those who lived and shaped them, are part of a new exhibit on display in The Bancroft Library’s gallery. Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is an immersive exploration of how ordinary people pushed the Bay Area onto the front lines of the environmental movement in the 20th century, with themes that resonate today.

Appetite for destruction

In 1953 — 70 years ago — The Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, began collecting and preserving the voices of people, through in-depth interviews, to tell the story of California and its place in the country and the world.

Although oral histories have been woven into Bancroft’s exhibits in the past, Voices for the Environment is the first to put them in the foreground.

The exhibit tells a nuanced story, unfolding across three sections, of environmentalism in the Bay Area through voices and vignettes, carefully curated by members of the OHC’s staff, and complemented by other artifacts from the library’s archives.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism

Where: The Bancroft Gallery, in Doe Annex

When: Oct. 6 through Nov. 15, 2024; the gallery is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and is closed on weekends and holidays.

See the event listing for more information.

Cost: Free

The first major milestone of the exhibit comes at the dawn of the 20th century. On April 18, 1906, the Bay Area was shaken into the new era by San Francisco’s earthquake and fire. The disaster decimated about 80 percent of the city, then the largest in the U.S. west of Chicago, and the devastation is depicted in the exhibit in harrowing historical photographs and in rare early footage recorded while the city was still aflame.

The effort to rebuild put the ancient, fire-resistant redwoods on the chopping block. The fire and earthquake, and the demands they posed on the environment, fueled a tug of war between environmental protection and economic development, and launched a wave of activism, said oral historian Todd Holmes, the exhibit’s lead curator.

In the exhibit, postcards from Save the Redwoods League, founded in 1918, appear near a photograph of women in the organization, on a tour of Humboldt County. Although often cast in the shadows of men such as Sierra Club founder John Muir, women, including UC Berkeley alums, provided much-needed momentum to the movement, carrying out advocacy work such as lobbying and fundraising.

“(Women) were the ones writing the letter campaigns,” said Roger Eardley-Pryor, an oral historian and co-curator of the exhibit. “They were the ones sending the notes to the congressmen saying, ‘Make these changes’ — even though they weren’t able to vote at the time.”

Fitting for an exhibit curated by the OHC, the spoken word pulses throughout the exhibit. But containing a multitude of voices in a single space presented a challenge. In another first for Bancroft, Voices for the Environment uses audio spotlight technology. Speakers, resembling flat-screen TVs, hang near three benches, allowing visitors to listen to the subjects’ stories, in their own words, as historical footage and photographs are shown on nearby monitors. By creating a “cone of sound,” each speaker delivers audio that is clear and crisp to people within earshot, but is muffled to people just outside of its range, preventing the voices from devolving into a distracting din.

In the section chronicling the early part of the century, visitors can watch rare footage of the earthquake and fire while listening to the stories of survivors, captured by a professor in the 1970s. The testimonies had been donated to Bancroft and were sitting in a vault until recently, when they were digitized. The exhibit is believed to mark the first time the voices of these survivors will be publicly heard.

People at the heart

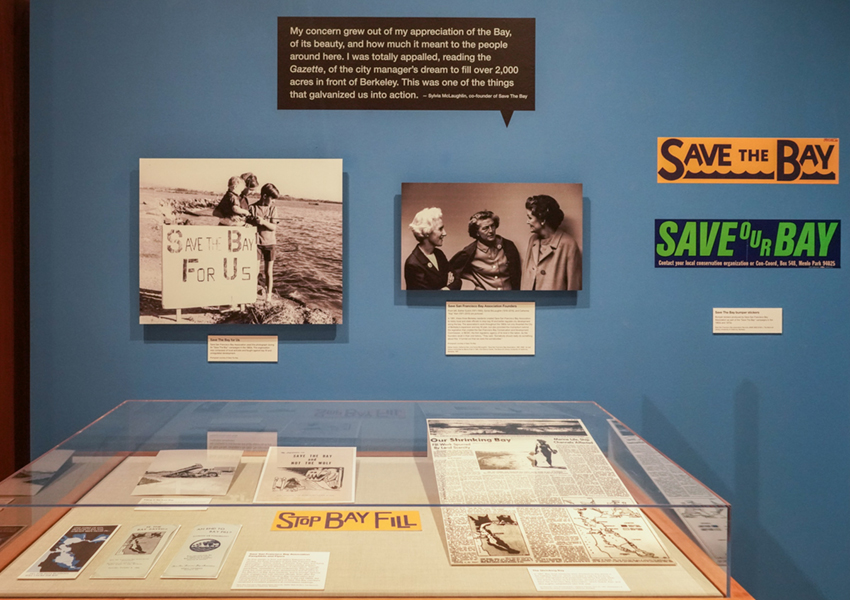

Toward the middle of the century, the push to pave the bay gave rise to the efforts to save the bay. Save San Francisco Bay Association was founded in 1961 by Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin, whose voices are prominently featured in the exhibit. Also on display is the Oakland Tribune article, with the accompanying map, envisaging a stark future for the bay — which set Gulick, Kerr, and McLaughlin into action. An array of photographs, stickers, and other materials that show how the organization, now known as Save The Bay, raised awareness for the cause.

“They said, ‘Somebody should really do something about this,’” McLaughlin recalls in an interview featured in the exhibit, reflecting on the efforts to fill the bay.

“It turned out that we were the somebodies,” Gulick responds.

Activism took on a new dimension as the end of the century drew near. The final section of the exhibit explores the environmental justice movement, taking aim at the unequal effects of pollution and destruction imposed by industry.

The Chevron refinery in Richmond, one of the largest oil refineries in the nation for more than a century, provides a stirring example of the disproportionate burden placed on communities of color.

A photograph stretching from floor to ceiling shows the refinery, black smoke belching from its stacks. Nearby, a poster with an illustration of a Laotian woman by artist Erin Yoshi depicts the unbreakable tether between individuals and their environment. Oil drums and a child on a swing set fill the space where her organs should be as smoke fills her lungs. The poster was created in collaboration with the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, a grassroots group that is leading the fight for environmental justice.

“It illustrates the way in which the built environment is being inhaled, literally, by the people who live there, and they are suffering from that, and their children are suffering,” said Paul Burnett, the OHC’s director and co-curator of the exhibit.

APEN was co-founded in 1993 by Pamela Tau Lee, who was born and raised in San Francisco, and whose voice is featured in the exhibit. In the decades since, the organization has drawn attention to those who are most vulnerable to the ill effects of industry in the Bay Area, including Richmond’s Laotian community.

Across the century, the environmental movement morphed, adapting to the challenges of the day. While each period featured in the exhibit has its own share of successes and setbacks, a golden thread ties them together: the power of individuals, lending their voices to make a difference.

“It was average people, just like us, and people in your neighborhood,” Holmes said. “And that’s how change happens.”

Out of the woods

Unlike a traditional exhibit, Voices for the Environment doesn’t end when you exit the gallery doors.

Visitors are encouraged to take history home with them. A three-episode podcast series, featuring interviews from the OHC’s collections and narrated by KQED’s Sasha Khokha, dives deeper into the themes and events from the exhibit. In the gallery, visitors can scan QR codes with their smartphones to listen to the episodes. The podcasts can be listened to anytime, anywhere, from high school classrooms to rush hour commutes. And, as a complement to the exhibit, curators have created a workbook, so students of all ages can learn about the environmental movement by engaging with the themes and primary sources on display. Through these efforts, the curators hope Voices for the Environment will have a life beyond its yearlong run.

“As interviewers, we probably have deeper knowledge of what’s in the Oral History Center’s archive and what we’re adding to the archive than anyone,” Eardley-Pryor said. “And we wanted to get that experience as curators out into the world.”

The OHC not only supports research at UC Berkeley, but invites everyone to listen to and learn from its trove of interviews, nearly all of which are free and searchable online, so they can peer through these windows into history.

All told, the OHC’s collection totals some 5,000 oral histories — about 30,000 hours’ worth of recorded interviews — including conversations with figures in agriculture, politics, science and technology, and the arts. In fact, the OHC is believed to have the largest publicly accessible oral history collection in the West, if not the country, and is the second-oldest program of its kind in the United States.

The OHC is “part of the fabric of who we are in the library,” said Kate Donovan, director of Bancroft and UC Berkeley’s associate university librarian for special collections.

“Part of the powerful work that we do in libraries is preserving stories and then making connections between people,” she said. “And I think that’s what these oral histories have the power to do.”